Impressions of the Armenians of Anatolia

To many Diaspora Armenians, the idea of Armenians living within the borders of the Turkish Republic varies from being an irrelevant factoid to a shocking revelation. The contemporary Armenian national identity is disproportionately shaped by the genocide of 1915, epitomized at one extreme by the fiery rhetoric of the contemporary Dashnak movement, intent on reclaiming land it views as rightfully Armenian. And yet, paradoxically, little thought is given to the Armenians already living on that very land.

One day I happened upon a discussion of reparations for the Armenian genocide online. A group of nationalistic young Armenians were trying to work out just how much the Armenian state would receive when the Turks inevitably capitulated to the overwhelming international consensus that they must repay the Armenians for their crimes with great swathes of land. The discussion was concluded (for no one saw fit to respond) by a lone Turkish Armenian:

“I don’t know if Armenians outside Turkey just ever considered how their hostile actions may result here for us. I believe past is past and want to live in a stable country which I was born to and grew up!!!What is the land to do with genocide, that’s why Turkey will never accept it, because they know that you want the genocide accepted only for the land. Who’s gone is gone, so who will live in the lands after Turks move again millions out of their home. Also, how can you ask for a land, which was never officially ours. There are still many of us living in different countries, so why not break up from U.S and make a free Armenian State there??”

Whether this perspective was seen as invalid, unrepresentative, or alien to the nationalistic Armenian readers is as irrelevant to me as how nationalistic Turks view Turkey’s various “traitors”. What is relevant to me is that the Armenians in Turkey be given a voice divorced from the bravado of the two competing nationalisms that each seek (in their own ways) to appropriate them for their own devices.

I cannot profess any special insight into the psyche, or any such exhaustive knowledge, of the Armenians living in Turkey. Indeed, my primary goal here is to dispel the myth of such a monolithic entity as “the Armenians” (an entity no more meaningful than “the Turks”). One might view this as a starting place, both for my own desire to write about Anatolian people and for the Armenian reader’s journey to understanding the Anatolia that continued to grow after their ancestors were forced to leave it. Even my own modest experience with and research on contemporary Anatolians (both “Turk” and “Armenian”) have aroused the curiosity of several Diaspora Armenian acquaintances. I can only hope to arouse such curiosity further. I can only hope that one day Istanbul is viewed as being as representative of the Armenian Diaspora as Beirut, Paris or Glendale.

The last time I was privileged enough to appear on Comrade Liana’s site, I was in Turkey, where I will no doubt have returned by next April 24. In the interim I have visited the ruins of Ani and looked across the border at Armenia. I have seen no new Armenian films and spoken to only one non-American Armenian (he is Lebanese, and a Dashnak).

It is with such dizzying credentials that I seek to outline for you what I know about Armenians in Turkey.

The Armenians of Istanbul, like the Jews of New York, are disproportionately successful and famous, due to their community cohesion and concentration within Turkey’s cultural and economic centre. They are able to boast such impressive figures as Hrant Dink, Onno Tunç, Nubar Terziyan, Hayko Cepkin, and Matild Manukyan (I also wish to express my deepest gratitude toward Sevan Nişanyan, whose excellent etymological dictionary I find myself using weekly). There are also political parallels with American Jewry: They are disproportionately left-wing in their voting patterns, but are by no means exclusively committed to the left. Indeed, right-wing Kemalism seems to be a comfortable choice for more affluent Armenian voters. The community is proud of its Caucasian roots even as it holds an important place in modern Republican Turkish society. There are those who desire nothing more than to be viewed as respectable Christian citizens of a Turkish state, and those who crave more public recognition of their distinctive identity, even calling for a secular representative of Turkish Armenians alongside the various religious leaders. There are even those who have forged a connection to the Kurdish people, having assimilated linguistically with them in the years after the genocide, all the while retaining their Christian faith. Hrant Dink’s widow, Rakel Dink, belongs to such a clan. There are those for whom, like a growing number of their Muslim compatriots, the European Union is a meaningless entity, and those who see it as presenting a path forward for the sort of Turkey they believe in.

But while the scattered remains of Anatolian Armenian-ness have flocked to Istanbul, there is still one other (admittedly tiny) concentration of Armenians in Turkey: Vakıflı.

During the Armenian Genocide, many Armenians took refuge in the predominantly-Arab southern regions of what would later become Syria. The populace of these regions was less than sympathetic to the Young Turk government, and has generally viewed the Armenians and their plight with sympathy. The French later occupied Syria, including the disputed Hatay province, which was eventually ceded to the young Turkish Republic by the French (a move whose legality is still disputed by the Syrian government). Rather than live under Turkish rule, most of the Armenians of Hatay moved across the border to French-occupied Syria, where they live to this day.

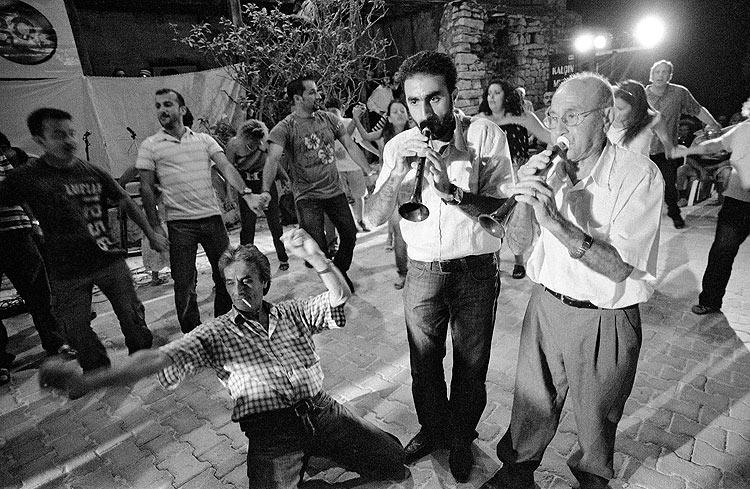

But one village chose to remain, making it the only Christian Armenian village in Turkey. This village is known as Vakıflı in Turkish, or Վաքըֆ in Armenian. Like most Turkish citizens living far from an important hub like Istanbul or Izmir, the Armenians of Vakıflı are often drawn toward these urban areas for work, but this village still remains for its younger generations to return to during the summers, a tiny testament to the post-nation-statist possibilities for the region.

Finally, there are the Hemshinli people, who are the most controversial group in such a discussion of Turkey’s Armenians, but in my view, the most important. The group in question are Muslims living in Eastern Turkey who speak a language that is undeniably a form of Armenian (their dialect can be heard in the film Sonbahar, made by Hemshinli director Özcan Alper). But their identity as Armenians is a bit contentious. Turkish nationalism generally dictates that they (like most minorities in Turkey) are Turks (either because they are loyal to the Turkish state or so that they might be loyal to the Turkish state), and their language has no bearing on that question. Armenian nationalism is not noticeably more forgiving, as it is an unspoken (sometimes spoken) rule that as Armenia is the first Christian nation that every Armenian is to be a Christian and exceptions are to be taken as eccentricity at best and treason at worst.

If you were to ask them, the answer you would get would depend on their political leanings. On the extreme right, they are offended by the implication that they have even a drop of Armenian blood, while the extreme left has been known to learn the Armenian alphabet so as to better connect to their lost brethren. Perhaps no group better captures the omnipresent contradictions in Armenian affairs in Turkey today quite like the Hemşinlis, whose ability to embrace and reject Armenian-ness so thoroughly is emblematic of modern Turkey’s inability to find simple answers to the Armenian problem, almost 100 years after what the other side has come to view as its defining moment.