Op-Ed: In Armenian Election Aftermath, Lessons Learned?

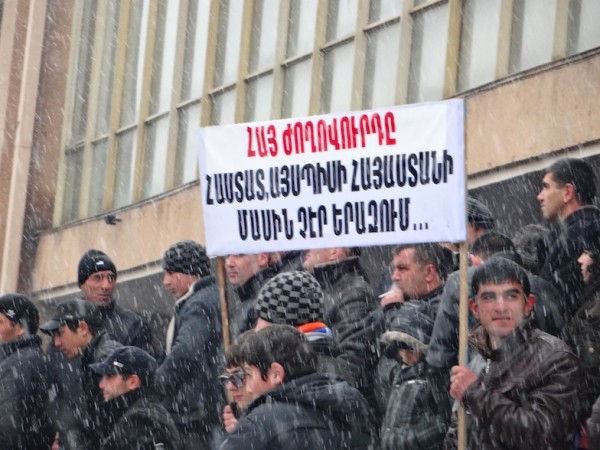

Yerevan residents at a post-election Hovannisian rally on Feb. 22/ Photo courtesy of author

The question on most people’s minds in Armenia since the Feb. 18 presidential elections, and the stream of protests that has followed, is what is Raffi Hovannisian going to do next? What is his plan? From one meeting to the next, one village to the next, that seems to be the paramount question. The 2008 presidential elections, when after street demonstrations by hundreds of thousands protesting against grossly falsified elections, Serge Sargsyan was inaugurated president are fresh in the minds of many, even if the sentiments remain unspoken. At that time the protests were quelled through state sponsored violence and a regime-imposed state of emergency. Underlying that big question are several that follow: How will violence be avoided this time?

What have we learned? And what are the options for Raffi Hovannisian and his team?

Though I have read numerous articles on the topic, it was Hrant Ter-Abrahamyan’s recent article that struck a chord with me. Most striking was that he addressed a question I have battled with since February 2008. When a regime is willing to use force against its own people, how do the people, as resolute and numerous as they may be, bring about change, without suffering bloodshed? And by change, in this context, I am referring to the more immediate type of “change,” of having the candidate who had actually won the election be declared the winner. Even if one is willing to consider bloodshed in the case of all out revolution, how does that change happen, when the regime’s resources are so much greater than those of the people? Except for Burma, where non-violent protests took place, more recent examples of the revolutionary waves of the Arab Spring which left thousands dead in its path and the ongoing violence in Syria are all too common.

But we would like to avoid bloodshed… how is it done?

Ter-Abrahamyan’s answer was quite clear. The instruments of potential violence, like the police and the army, must be neutralized, either through growing differences within the regime itself or by having leaders of these institutions themselves joining the opposition. Ideally, I would say, the people, and whoever is leading them, must be able to convince the leaders of the police and the army NOT to use violence and force against the people. This makes sense to me. The first Armenian president, Levon Ter-Petrosyan, who would have likely won the 2008 elections had they been free and fair, tried that approach back then.

He worked with two deputy ministers of defense, Lieutenant-General Manvel Grigoryan and Mr. Gagik Melkonyan to try to attain the support of the army for the people or at least to make sure that violence and force would not be used against the people. He seemed to be making some progress initially. It obviously and unfortunately fell through, and at the end violence was used against the demonstrators. Even then, his strategy to co-opt the power structures was part of his plan.

What is happening now on that front? I have no idea if part if Mr. Hovannisian’s plan includes talks with the army or police chiefs; hopefully it does as one method of trying to guarantee the security of the people. We know, nonetheless that Mr. Hovannisian is consistently, repeatedly and directly talking to the police at the rallies; he speaks with them with respect and his language is inclusive of them: he tries to make them see themselves as part of the people’s struggle for legitimacy, or at least, not their enemy. And at least in Gyumri, they were listening. But that was no surprise, it was Gyumri.

There is an approach, in this respect, that Mr. Hovannisian is taking that perhaps Ter-Petrosyan did not, and I wonder if this additional dimension could possibly produce a different outcome. Let me backtrack for a moment. Ter-Petrosyan’s team spent significant effort on the appeal to the constitutional court. We will see what Mr. Hovannisian’s response to the Central Election Commission’s confirmation on Feb. 25 of Serge Sargsyan’s re-election will be; he has strongly implied that he will appeal to the Constitutional Court. Ter-Petrosyan stated in 2008 that the world was watching, though it turned out the world turned a blind eye to the true principles of democracy and human rights, and followed their own interests; similarly, the reports of the international election monitors turned a blind eye to the truth. Battles for the respect of the people’s will were also waged at the level of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. Beyond the elections results, that campaign brought multitudes of human rights violations that followed for years to the attention of what is known as the “international community,” to no avail. Maybe Mr. Hovannisian’s team will battle on the same fronts; but it is also possible that the team may have learned the uselessness of those observers and reports, and will focus there efforts differently.

Residents in Gyumri, Armenia’s second largest city, hold up signs and participate in a Hovannisian rally, a city in which he secured a majority of the vote./ Photo courtesy of author

Why is this important?

Because from the very beginning, Mr. Hovannisian has included a factor, possibly a force, that Ter-Petrosyan did not: the Diaspora. Even at the first official public protest meeting on Wednesday February 20th, one of the speakers at Liberty Square was a diasporan, Garo Ghazarian, who is the chairman of the Armenian Bar Association in the United States. In fact, Mr. Ghazarian wrote a letter addressed to Mr. Sargsyan on February 1, 2013, urging him to “deliver to the Armenian citizenry its constitutional right to free, fair and democratic elections.”5

And while the Ramgavar Party congratulated Sargsyan almost immediately, the ARF or Dashnak party issued a statement that the party stood for the “will of the people.” In fact, Asbarez, one of the main ARF papers in the Diaspora, has been covering the events, and overall has been quite positive regarding Hovannisian. Days before the election, the ARF made a statement and the article covering it is titled “ARF says vote NO to Sarkissian.” Days later, even Karen Yegparian, a regular columnist, mentioned THE elections, though briefly, in his column, and an interview with an ARF member in Yerevan was published referring to the elections as giving ‘hope’ and ‘turning a new page.

The ARF joined Hovannisian’s movement within days.

Mr. Hovannisian is, as has been said, more Dashnak in some ways than the Dashnaks themselves. His approach to foreign policy, specifically his focus on genocide, reparations and recognition of NKR, speak to the nationalistic hearts of the Dashnaks. While obviously a completely different political party, some ARF members and followers in the Western world may feel closer to his politics than they do to the policies of their own ARF members in Armenia. And if the ARF chose to support him with their full might, such a move could garner a lot of support and clamor from its diasporan supporters.

I don’t know if this additional factor integrated in Mr. Hovannisian’s approach could make a significant impact. I don’t know if it’s a safe factor to bring in. I have never hidden my distrust of diasporan organizations’ involvement in Armenia’s politics, especially bringing the diaspora into processes to legitimize or de-legitimize elections in Armenia. Still, it remains a factor. And could it be enough to change the answer to my initial question or, at least, to nudge it slightly.

P.S. Of course, one possible solution to Mr. Hovannisian’s challenge is that Mr. Hovannisian accepts some position in Sargsyan’s government. But that, that and the implications and sequel of such a deal, constitute the theme of a whole separate volume.

Tzitzernak is the pseudonym of an opposition blogger who regularly writes about human rights and social justice in Armenia. The author prefers to remain anonymous.