Glimpse: Lives of 19th Century Armenian Women

1

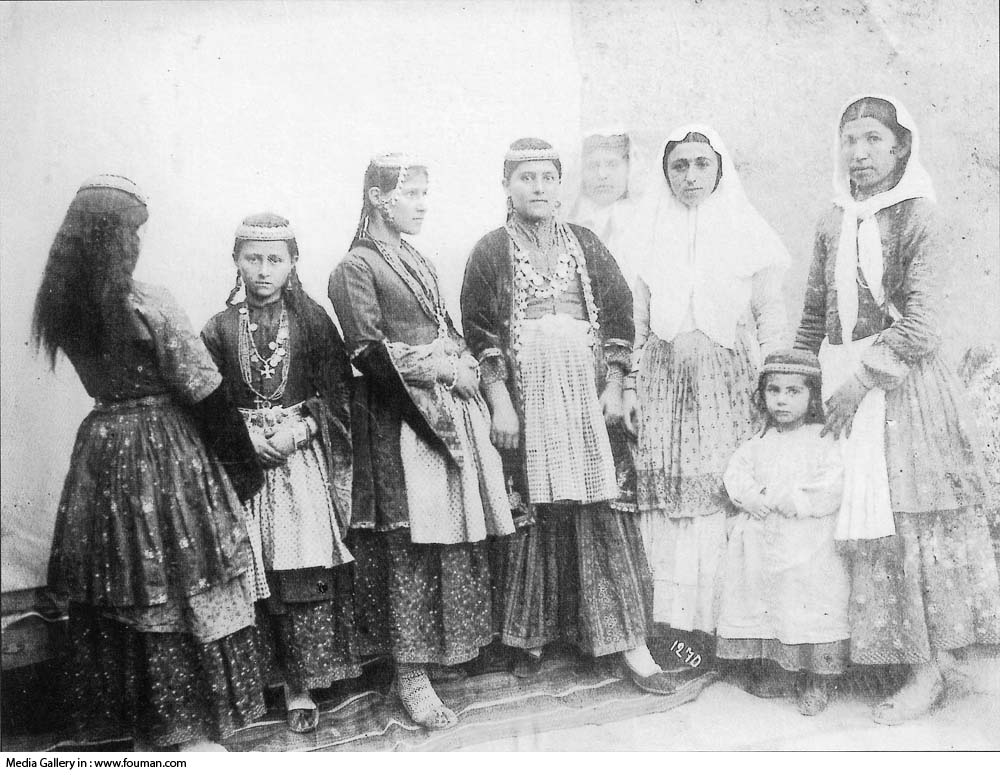

Armenian women in short jackets and straight skirts,1881/ D.N. Yermakov,Kunstkamera Museum

2

Armenian woman surrounded by textiles in the late 19th century, via http://tea-and-carpets.blogspot.com

3

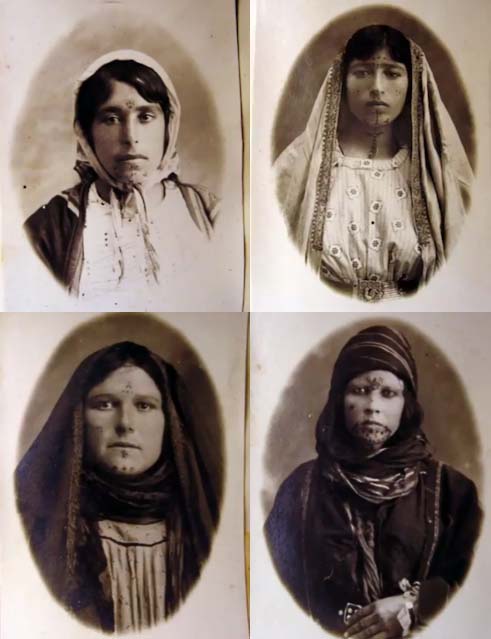

Armenian women during the Qajar era in Iran, 1890s/Wikimedia Commons

4

A painting by Frederick Arthur Bridgman of an Armenian woman during the Ottoman Empire

5

Armenian woman from Shemakha in fine dress, 1883/Kunstkamera Museum

6

Two Armenian women pose together for a studio portrait/Photographer unknown

7

An Armenian woman in traditional dress/ Pierre di Gigord

8

An Armenian merchant's wife, 1880s/Photographer unknown

In “A History of Armenian Women’s Writing, 1880-1922,” author Victoria Rowe discusses novelist Zabel Yesayian’s impressions of the lives of Armenian women in the 1880s and 1890s.

“In her autobiography, Yesayian noted that in her youth, many of her female friends lamented the fact that they had little freedom. They ‘wanted to be educated, to participate in ordinary life, go out with male friends, meet, travel,’ ” writes Rowe. “Her friends did not know how to change their circumstances and often became depressed.” They began to read the works of Srpouhi Dussap,the first female Armenian novelist and feminist writer, trying to find a solution to their “disturbing questions.”

The lives of Armenian women in the 19th century and the women’s movement have by and large received little attention. In fact, two men, Vartan Hatsuni and Yeprem Poghosian, members of the Mkhitarists, the Armenian Roman Catholic religious order produced the only available works on women’s history, according to Rowe.

While the women’s movement began after Soviet independence and has gained ground in the last decade, it has also rediscovered its lost history through social media, NGO work and documentaries, giving credence to its influential roots in the late 19th century.

Its beginnings can at least somewhat be traced back to two groups that emerged in 1879 in Istanbul: “The Educational Society of Armenian Women’ and the ‘Patriotic Society of Armenian Women’, according to the 1999 Women State Report of Armenia by the UNDP. “They became the largest, longest lasting and most influential among the multitude of other large and small women’s organisations and had a profound impact on the women’s movement and in the history of educational activities,” despite the 1915 Armenian Genocide putting a stop to their activities.

This article argues that the Armenian women living in Istanbul are confined to domestic and communal spaces, and that the roles of symbolizing collective territory and identity, and of cultural reproduction of the community, are mostly associated with women. The data and observations we explore here are based on a field survey of Turkey’s Armenian community that was conducted in Istanbul between November 2004 and May 2005. Evaluation of this survey based on both quantitative and qualitative methods allows us to draw some conclusions about the roles of Armenian women in the reproduction of Armenian culture. Women’s roles indirectly influence Armenian identity, creating the conditions for its survival.

In “Armenian Village Life Before 1914,” authors Susie Hoogasian Villa, Mary Allerton Kilbourne Matossian outline the daily life, roles, rituals and cultural significance of Armenian women in the 19th century.

Marriage, pregnancy and child birth, especially sons, gave the Armenian woman status as a wife and mother. “The wedding ritual celebrated one’s coming of age,” the authors write. “The bride began to cover her hair, as did all adult married women. The groom established his potency…during weddings, the girls family came for achkee looysee “congratulations” and was served pastry. Then the boy and his friends came to the girls house and were treated to an omelette served with syrup. There was a ceremony when the boy presented the ring, which was used for both the engagement and the wedding.

Arranged marriages were common. Often, a ges-bsag or “half-wedding” was performed at the girl’s house, “a ceremony which was supposed to make it impossible for the girl’s parents to substitute an ugly daughter for the promised bride.”

Other details in the book include how widows made their living traveling and baking toneer bread and how women in Eastern Armenia preferred the color red, believing that it warded off evil.

A 2009 article published in “Gender, Place and Culture,” titled “Armenian women of Istanbul: notes on their role in the survival of the Armenian community” argued that Istanbul-Armenian women were confined to domestic and communal spaces, echoing the sentiments in “Armenian Village Life Before 1914,” that the preservation of cultural identity were associated with women.

“Women’s roles indirectly influence Armenian identity, creating the condition for its survival,” the abstract says.

Next door in Iran and Azerbaijan, the same details are echoed. Concentrated mostly in Azerbaijan and Isfahan, Armenian women took care of the household, spent their evenings doing needlework with older women spinning wool and preparing thread to weave rugs in the winter, says a comprehensive entry in Encyclopaedia Iranica. Girls married around 15 or 16 and did not just “merely physically reproduce their children,” but were the “major influence in the lives of their children—they were also the socializers of children, reproducing the culture through dress, behavior, and use of language, as well as culinary and other customs.” Their dress and other social customs were often not distinguishable from those of Muslim women.

The piece also notes that the wine trade was in the hands of women, “as alcohol could not be sold openly and was therefore, sold out of the home, the seat of the female authority” and that women were active on the theater stage in Iranian cities, establishing their own theatrical groups, traveling and performing in Istanbul, Iran and Egypt.

As modern Armenian women’s movements are shaped and moved in the Republic of Armenia and Diaspora, much of its roots and the day to day lives of Armenian women and how it correlates to today, is also increasingly revealed in the process.