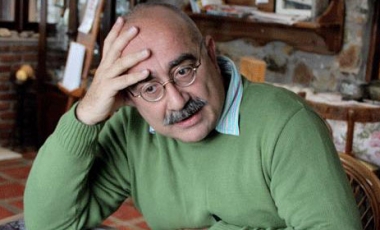

Q & A: Sevan Nisanyan, Turkish-Armenian Blogger Sentenced for Blasphemy

A criminal court in Istanbul has sentenced Turkish-Armenian journalist and commentator Sevan Nisanyan to 13 and a half months in prison for a post Nisanyan wrote last September in response to the release of “The Innocence of Muslims,” what was dubbed to be an anti-Islamic film – and its aftermath, when violent protests broke out in Egypt and other countries, leading to over 50 deaths.

A criminal court in Istanbul has sentenced Turkish-Armenian journalist and commentator Sevan Nisanyan to 13 and a half months in prison for a post Nisanyan wrote last September in response to the release of “The Innocence of Muslims,” what was dubbed to be an anti-Islamic film – and its aftermath, when violent protests broke out in Egypt and other countries, leading to over 50 deaths.

Nisanyan, who argued that speaking disrespectfully of the Prophet Muhammed does not constitute “hate speech” was legally sentenced under article 216 of the Turkish Criminal Code , “Denigrating the religious values of a group.” The article states, “Any person who openly disrespects the religious belief of group is punished with imprisonment from six months to one year if such act causes potential risk for public peace.”

In a blog post this week, Nisanyan outlined the the single sentence in his article last year that touched on the Islamic Prophet Muhammad:

It is not “hate crime” to poke fun at some Arab leader who, many hundred years ago, claimed to have established contact with Deity and made political, economic and sexual profit as a result. It is almost a kindergarten-level case of what we call freedom of expression.

The sentence was condemned by Reporters Without Borders who called it a “grave violation of freedom of information and sends a threatening message to fellow journalists and bloggers that is unacceptable. The journalist advocacy group encouraged that the sentencing be turned over on appeal. “We have often hailed the gradual weakening of Turkey’s Kemalist – secularist, nationalist and militarist – taboos but democracy will not benefit if they are replaced by a new religious censorship,” the group wrote in a statement.

This isn’t the first time in recent memory that Article 216 has been enacted. Renowned Turkish pianist Fazil Say was given a 10 month suspended prison sentence under the same code for comments he made on Twitter. Nisanyan, a noted columnist and successful author of travel books was finishing a doctorate in political science at Columbia University when he returned to Istanbul for a vacation, started a computer company and never left, according to a 2001 New York Times article profiling his foray into restoring and operating guest houses in Sirince.

He took some time out to speak to Ianyan Mag about his recent sentencing, the freedom of speech debate and the situation Armenians and other minorities face in Turkey today.

Q. Receiving criticism for your writing and thoughts is something you’ve had experience with in the past – how do you deal with this? Do you take any of these threats seriously, do they scare you?

A.I receive a daily deluge of extremely graphic insults and death threats. One gets used to it after a while. They do not really scare me. As far as I know no politically-motivated assassination has ever taken place in this country unless ordered from high up. I doubt that in the current atmosphere the powers that be have either the inclination or the courage to create another Armenian martyr.

Q. Prosecutors have accused you of “overstepping the boundaries of freedom of speech and criticism.” What is your response to this accusation?

A.The quality of legal education in Turkey is poor. Evidently this prosecutor was under the illusion that saying something mildly distasteful to the prevailing public opinion is beyond the boundaries of free speech.

Q. You previously said, “Here I am an Armenian doing something no Armenian has done in a Muslim country. This is really the height of boldness, of impudence. This is something you are not supposed to do.” How did your ethnic background play a role in this prosecution and lengthy sentence you received?

A.I believe it was the key issue. People are simply not used to a member of a non-Muslim minority to speak boldly and coherently on sensitive national and/or religious issues. It drives some people raving mad.

Q. What kind of experience have you had as an Armenian writer in Turkey, or just as a citizen of Turkey? What challenges do Armenians or minorities in general face in Turkey today?

A. Prejudice and ignorance are still rampant, but things have improved vastly within the last decade. Goodwill is now the dominant note among opinion leaders. I have received some very positive, very encouraging endorsements from the better-informed segments of the Turkish public.

But even there, you find this underlying sense that an Armenian should never come so openly forward. You know, “we all love our Armenians, but we like them nice and soft.” That about summarizes the dominant attitude.

Q. I noticed that some Armenian Diasporans on social networks have compared what has happened in your case to that of Hrant Dink, calling for the State Department to protest your sentencing. What kind of similarities, if any, exist between you and him?

A. A hate campaign was systematically mounted against Hrant over a period of two years. There was judicial harrassment, barking mobs, death threats and terrifying headlines in the trashy press. My experience has been very similar so far. Except that Hrant was attacked primarily by the secular nationalists, and I am attacked mainly by the religious camp. These are considered the opposite poles of the political spectrum here.

Q. You have vowed to appeal your sentence. What do you think or hope will come of this?

A.It is an outrageous verdict in legal terms, so I expect the higher court may throw it out. What they will do next, if that happens, is to harrass me on some other, preferably non-political charge. I have a dozen other criminal cases pending on silly bureaucratic charges. That has been going on for almost twenty years now, and I doubt they they will give up any time soon.

Q. In your article, you said you argued that hate speech is only criminal if it actually puts the rights or security of a vulnerable group in jeopardy. You wrote the blog post in response to the furor around the film. What in particular struck a chord in you and compelled you to write about it? Did you expect the commotion it caused?

A.There was an uproar here last year over that cheapo Muhammed film, and several top politicians close to the prime minister took the opportunity sound out a new law on Hate Speech, which was meant to curtail “disrespect” of Islamic values. I thought then (and I still think now) that’s a serious threat to public freedoms here. That urged me to discuss the idea of “hate speech” and its limits.

I must confess that this article by Daniel Pipes was the immediate source of inspiration for my note. I am not a fan of either Mr. Pipes or Fox News. But I felt they had a good point here.

Q. What are your thoughts on the freedom of expression (or seriously lack thereof) in Turkey today?

A.Historically, the military establishment has been the biggest threat to civic rights and freedoms in this country. The government of Tayyip Erdoğan has done a great job of dismantling that apparatus of military dominance. It is a pity that now a counter-wave of Islamic bigotry seems to be on the rise.

Q. You have previously served time in jail – what was that experience like, if you were to sum it up?

A.It is like being at a particulary stupid boarding school. Nothing really terrible, just tedious and sometimes infuriating. I had plenty of time to concentrate on my linguistic work. The first edition of my etymological dictionary shaped up in jail. A few months in the cage now might be a good chance for me to work on the next revised edition.

Q. You mention in your latest blog post that several individuals around Turkey filed complaints about the article. Do you have any idea who they are? And what does their offense at your post mean in the larger scheme of things?

A.Muslim opinion was muzzled in this country for almost three generations. Now that the muzzle is off, I think some people are testing their newly acquired voice.