Armenia’s Suicide Spot: The Kievyan Bridge

1

This summer, activists in Armenia left messages of support on the Kievyan Bridge, a popular suicide spot in the country's capital, Yerevan./by L.Aghajanian

2

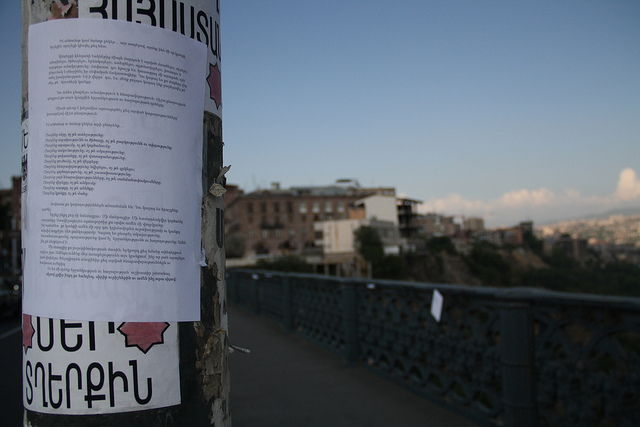

Residents who were passing by stopped to read the taped letters./by L.Aghajanian

3

With a worsening socioeconomic situation, the Republic of Armenia has seen a 20 percent rise in the number of suicides in the last few years./by L.Aghajanian

4

The letters of support urged potential suicide victims to "choose life," instead of death./by L.Aghajanian

5

"You have the ability and means to choose. The right choices will open doors to success and happiness," the letters urged./by L.Aghajanian

6

The young activists taped and strung letters on both sides of the bridge as well as to nearby posts./by L.Aghajanian

7

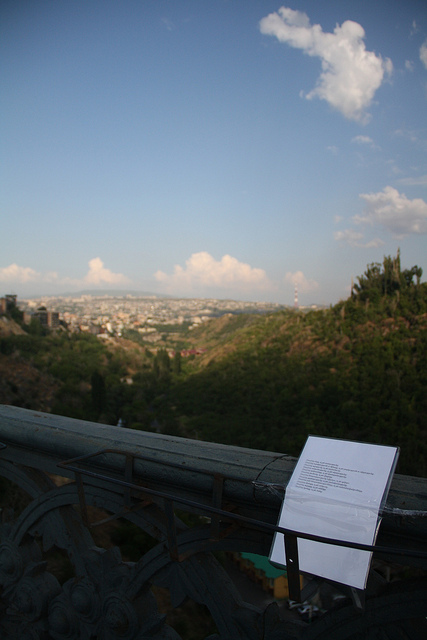

A letter of support for suicide victims overlooks the steep drop from the Kievyan Bridge./by L.Aghajanian

8

Activists securely tape letters on the railings of the Kievyan Bridge, a popular suicide spot in Yerevan to persuade those who are considering jumping to step back from the ledge./by L.Aghajanian

The buzz of cars making their way across the Kievyan Bridge never comes to a lull. In fact, the more you hang around, the louder it gets. Wild herds of Ladas pinch, honk and pull at each other, until the vehicular cacophony adds human voices to its ensemble; angry voices, who leave their cars to berate one another in the middle of late afternoon traffic while honks drown out their insult-laden hollers. Below, the bridge’s sturdy beams dig into a gorge. Above, its delicately carved blue-gray railings swirl beneath the skyline to a time when Yerevan was the capital of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Armenia, a time many of the city’s residents nostalgically wish hadn’t ended. Over three sun-drenched months from Yerevan to Vanadzor, I ask them why. “Because life was secure, because we had jobs, because at 70-years-old, I wouldn’t have to sell old china and Soviet-era trinkets to tourists every weekend just so I can make sure my family eats,” they say.

But Armenia’s socioeconomic circumstances, where around 30 percent of the population hover under the poverty level, has resulted in more than lack of jobs and security. Armenia is also lacking in mental health services, which, when provided, are sometimes of questionable quality, according to a 2009 World Health Organization Mental Health System report. Rural areas lack modern medical technology and human resources. The lack of trained social workers limits providing services at a community level. Psychiatric care is exclusively provided in specialized mental health institutions. Only five outpatient mental health facilities are available in the country.

Back on the Kievyan Bridge, the traffic swells. Years ago, the 1950s era bridge went through repairs. Now, it’s being used consistently as a means to an end: suicide. In fact, there’s been a 20 percent rise in suicide rates from 498 in 2009 to 592 in 2010, according to the National Statistical Service.

Suicide bridges; other cities have them too. The Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco is the most popular suicide bridge in the world. Pakistan’s 100-year-old Netty Jetty Bridge in Karachi has seen at least a thousand jumpers. The Nanjing Bridge in China has become a notorious site for those looking to end their lives, though a rogue angel has been saving would-be jumpers for the last few years.

In Armenia last November, 55-year-old Pavel Vardazaryan took his own life. Soon after, a student’s corpse was found under the bridge. In May, a 40-year-old man survived a suicide attempt from the bridge. On June 17, a young women in her twenties jumped from the bridge, leaving a suicide note behind. “I’ve grown tired of you,” the note read. “I abhor everything. I’ve become a slave at your hands, death is my only friend. Live well, now and forever.”

A few days later, a group of activists descended on the bridge in the afternoon. The stream of cars endlessly rode across the bridge. They brought tape, string, scissors and copies of encouraging messages on 8 1/2 by 11 paper in an effort to stop someone from jumping or again, or at least, hoping that those set on taking the plunge have a change of heart. They weren’t many, but they were determined, set on filling a small, immediate space in a very wide gap of mental health services the only way they knew how. Armenia is in dire need of psychological services, they told me. People need help, they need someone to listen to them. Suicide here knows no age, they said. Young people, distraught with their future, and sometimes heart broken see it as the only way out. The elderly, worried about the burden they bring, take their life away to make their childrens’ lives easier.

We walked and talked. On each end of the bridge, they taped and strung the following letter:

“My familiar or unfamiliar friend…these lines, that at one time returned life to me, I’ve decided to now gift to you.

Of all the Universe’s living things, only human beings have been given the abilities of thinking, loving, ruling, laughing, imagining, creating, arranging, talking and praying. Believe that you are a miracle, a perfect creature who has the ability to manage his own destiny. You can turn your thoughts into reality. And in the end, you, me, all of us can improve our lives and the lives of others.

You have the ability and means to choose. The right choices will open doors to success and happiness. You have wisely use your abilities to make the right choices.

My familiar or unfamiliar friend, let’s choose.

Choose love, not hate

Choose love, not hatred.

Choose joy and laughter, not sadness.

Choose creation, not destruction.

Choose healing, rather than wounds.

Choose to devote, not deprive.

Choose activism, not apathy.

Choose the possibilities, not limitations.

Choose to rise, not fall. Choose prayer, not curses.

Choose life, not death.”

As the stark white paper covered the bridge’s blue-gray rails, those who passed by stopped, stared and then approached to try and understand why this group of young activists were furiously taping messages between two lanes of buzzing traffic. Some read and left. Others read and laughed, chuckling at the absurdity of what was going on around them and peeling off the messages in the process. Two smirking teenage boys, not able to process the gushy verses asking potential victims to “choose life,” began to ask the activists what the point of it all was.

As the sun came down, the group wrapped up and made their way towards downtown Yerevan. A few days later, most of the papers were gone.

The suicides haven’t stopped, nor were they the first ones to occur. In September, Yana Manasyan, 28, a resident of the Narekatsi neighborhood in Yerevan’s Avan administrative district, committed suicide by jumping off the Kievyan Bridge.

Two days ago, local media reported that a 40-year-old man committed a suicide by jumping from Kievyan bridge in Yerevan. His identity remains unknown.

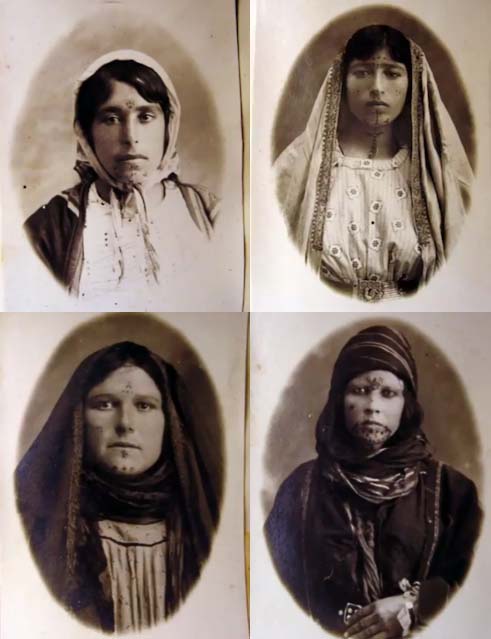

In 2009, Armenian photographer Karen Mirzoyan produced a portrait project of those in Armenia who had attempted suicide and later turned their lives around. Watch him talk about his project and its personal implications here: