Nancy Agabian on Growing up Queer, Feminism and Armenia

Nancy Agabian is a woman with many different titles. To sum her up as a writer wouldn’t begin to explain what she does and who she is. In this interview, Nancy talks about her past and recent work, her experiences in Armenia, the struggles she faced as a queer Armenian-American feminist and more. She also has a message for today’s Armenian youth: “Be proud of who you are as an Armenian, but don’t limit your education and development to the Armenian community,” she says. “Learning about diversity in people, places and ideas will only make you more whole. If you feel isolated, know that there are many diverse Armenians out there, including queer and feminist Armenians, so please reach out through the internet to find us.

Q: Your two books, Princess Freak and Me as her again, are about your identity as a queer Armenian-American feminist. What inspired you to write about your identity?

A: When I first started writing, I didn’t set out to write about identity as much as the conflicts I was experiencing in my life. It was 1991 and multiculturalism was a predominant force in the art world in L.A. In order to find community I joined a multicultural poetry workshop for women, where everyone was writing about their cultural background, and this gave me the space to express what I had been experiencing as a young, overprotected Armenian American girl. It made sense to look at the messages I was receiving as a young woman – about the body, sexuality, life choices with work and partner – and how they connected to Armenian cultural values. I did this for about five or six years, through poems, short prose and performance art pieces, and this work was collected into Princess Freak.

Later, when I was 30, I traveled with my aunt to the village of my grandmother in Turkey. From my aunts’ stories about our family, I realized there were some parallels among the lives of my female relatives striving for independence. I wanted to take a look at the reason why I left my family, and in particular, why I had needed independence from them as I was growing into a feminist and discovering my bisexuality. So I returned to the East Coast and attended Columbia University to research my family history, including the genocide and my grandmother’s particular history as a survivor. Me as her again comprises this search across the generations.

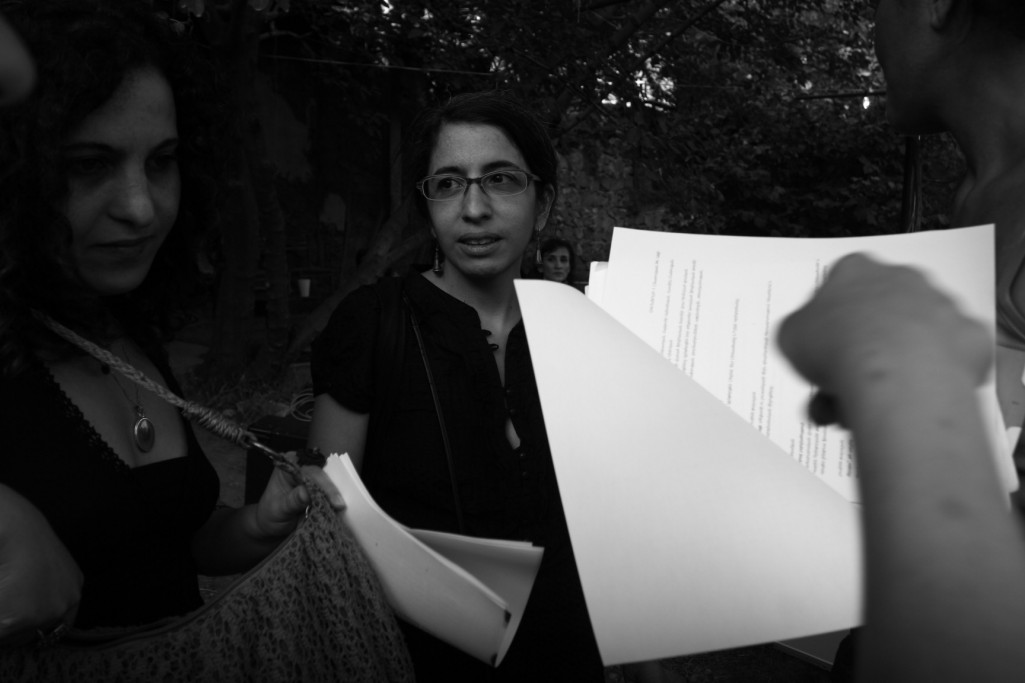

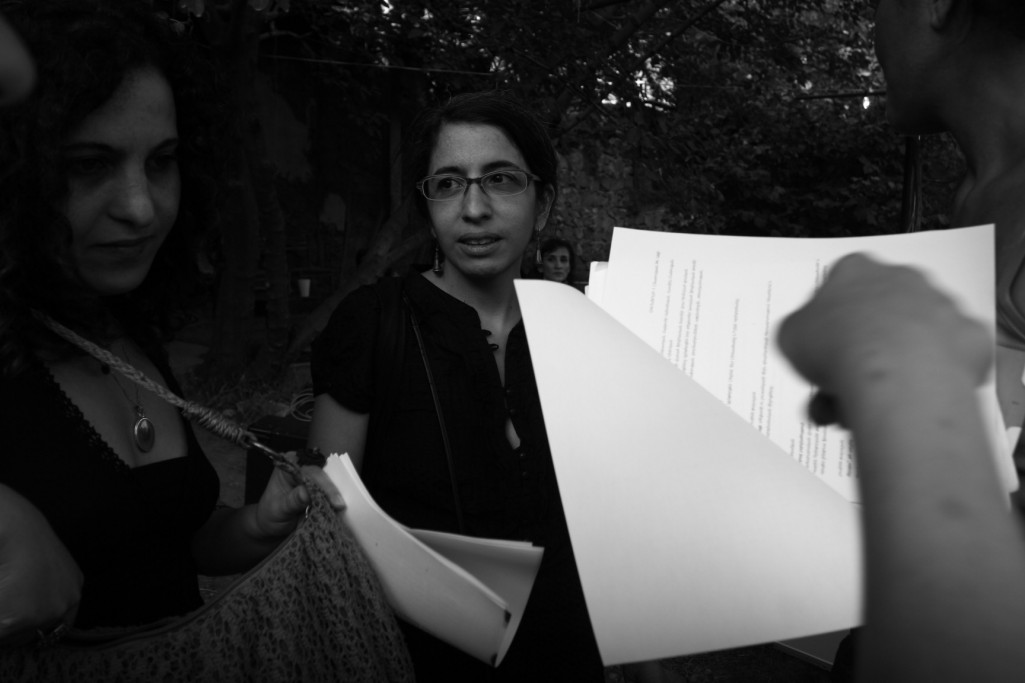

Nancy Agabian at a “Physical Translating” workshop in Yerevan/ by Anahit Hayrapetyan

Q: You have been to Armenia quite a few times. Can you talk about how it all began? How was your experience and what were you working on?

A: Shushan Avagyan, author and translator, translated and published some of the poems from Princess Freak in Bnagir, a progressive literary journal. They were noticed by the director of Utopiana, a political arts organization, who then invited me to Yerevan to do a performance at a feminist conference she was organizing in 2005. I participated in this event and listened to philosophers, sociologists, activists and artists from Europe and Armenia, and learned directly about the limited role of women in Armenia in public, political and professional realms after the Soviet collapse. I was there just a week but I became so fascinated by the struggles of this changing society. So once I finished Me as her again, I decided to spend some time there and teach creative nonfiction as a means for self expression and actualization – first steps in social change.

In 2006-07 I was in Armenia on a Fulbright to teach in the English department at Yerevan State University, which was almost entirely women. Very few students were serious scholars; most young women expected to marry and have a family as their primary life goal instead. I also came to learn more about corruption from this experience, in hearing about the systems of bribery and nepotism that allowed undeserving students to not just pass their classes but to receive top marks. My friends in the department and some of my students really lamented this situation; they were quite troubled by their role in it, and they seemed to feel quite powerless in changing it.

That summer of 2007, I had received a grant to lead a writing workshop for women with Utopiana and the Women’s Resource Center. We talked and wrote about family, identity, work, sexuality, societal messages, etc.; our commonalities and differences in thinking contributed to our discussions and our writing. There were two queer women in the workshop, and they discovered that they knew a few other queer women in Yerevan who were also artists. They all joined together to found WOW, the Women-Oriented Women’s collective, which has grown to become Queering Yerevan, an activist organization that includes men and women, gay and straight.

Q: What are some of the issues you’ve faced and techniques for overcoming some of the struggles you’ve faced?

A: Growing up in a predominantly white town in the 70s and 80s, I held a lot of shame and self-hatred for being Armenian; writing helped me through this. In particular, writing among a multicultural group of people made me realize how much Armenians’ history of oppression was important – that it told an important human truth that others could relate to and learn from. I also dealt with a lot of alienation from the Armenian community. The traditional expectations for women didn’t connect with the goals for my life. Though my parents were overprotective in my social development, they were very encouraging of me to find my life’s calling professionally, and they were also quite liberal politically. But coming out to them as bisexual was so difficult, since the Armenian community they were raised in and still belong to has so little language and awareness to talk about queer identity. And in general, it’s difficult in Armenian culture to find a forum to talk seriously and thoughtfully about sexuality or the body.

Agabian (center) prepares to present at the “physical translating” workshop /by Anahit Hayrapetyan

In 1999, I discovered the Armenian Gay and Lesbian Association soon after I moved to New York; this was a revelation because for the first time I was meeting other LGBTQ Armenians. At one point, I found myself in a rap group with two gay Armenian men, discussing the troubles we had with our families in coming out. We also did forms of activism, like attending Armenian Church services at St. Vartan’s Cathedral and protesting a lecturer at the Armenian Prelacy in New York who was arguing against gay marriage.

As I have been writing about my current relationship with an Armenian man in my book about my experiences in Armenia, I found myself shaping the body-based writing workshop for women in Armenia that would help me to express myself. The director of the Women’s Resource Center suggested the topic, so it was obviously a theme she thought many women would value. But the group helped me to overcome some of the fears that I have about writing about the body, particularly in connection with a partner. This led to my performance “Family Returning Blows”, which looks at attitudes around domestic violence in Armenia, as well as the history of violence I have experienced in my family and relationship.

So I suppose the tactics I have used for overcoming my struggles involve finding support in community and breaking silences in writing.

Q: One of the issues that progressive youth have found is difficult to address amongst our peers is the issue of sexuality and questions of homophobia in the Armenian community. What advice could you offer on how we can start a dialogue and address the importance of these issues?

A: I think the GALAS in L.A. has done a great job with this, with their yearly conferences, so I advise young people to attend that event or to collaborate with GALAS to include an event within their conference specifically about this topic.

I also think one way to discuss homophobia is through sexism – that part of what contributes to homophobia is the conservative expectations we have for men to ‘act like men’ and women to ‘act like women’. Some of the anger towards men who are gay stems from a response to their feminine attributes, which are somehow seen as weak or negative. Anger towards women who have more masculine attributes seem to be rooted in a kind of territoriality or misconception that butch women want to be men. Transgendered people are probably the most misunderstood, because with such inequities of gender in our culture, it’s hard for Armenians to understand that a man could be born in a women’s body — or vice versa – and would feel the need to enact that reality. So I think the Armenian women’s organizations and queer Armenian organizations could be joining together to educate people since the fear and misconceptions they are battling about gender are very similar. Perhaps reaching out to these groups could help channel resources to start a dialogue on the connections between sexism and homophobia, and what these forms of discrimination have in common with racism or other forms of prejudice that Armenians deal with.

Participants at the workshop read their work as Agabian listens from the front row/by Anahit Hayrapetyan

I know GALAS has done work with the parents of their members. On the East Coast, our numbers and resources are limited, so we haven’t done as much. But I have always wished we could start an Armenian version of PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). I think Armenian parents of queer kids are more isolated than their children; the kids can find each other online and at local LGBTQ events, but Armenian parents who are active in their communities face an incredible silence around the issues. They deal with shame, this entity that has such powerful psychological currency in Armenian communities and families. In some ways, it’s worse for parents to face the scorn of their communities than to accept the reality of the kid’s sexuality and what it means for the future of their family. If it weren’t for the judgmental eyes of the community, parents might have a better time accepting their kids’ reality. And if they had a group of Armenian parents facing similar issues, they wouldn’t feel so isolated and could find a means to battle the shame directed at them. So I would say reaching out to PFLAG might give progressive youth ideas for how to counter homophobia in the Armenian community, since our families are such a central part of our culture.

To keep up with Nancy, follow her here.

Agabian reads her work while the crowd listens on/by Anahit Hayrapetyan

This article is part of a series written in honor of International Women’s Day

About the author: Born in Turkey and raised in Los Angeles, Nora holds a B.A. in Psychology from the University of California Los Angeles. She is currently finishing up her M.A. degree in Counseling at Loyola Marymount University and works part time as a counselor intern at Arleta High School’s Social Justice Academy, where she practices her counseling and social advocacy skills. She loves chocolate, poetry and enjoys riding her bike through the smog-filled streets of LA.