Slideshow: Chechnya’s Forgotten Armenians

I was in Grozny to see my old friend Timur, and along the way I decided to use the opportunity to search for my Armenian relatives buried there. My great aunt and her daughter had died in Grozny in the 80s, and the rest of their family had moved away as a result of war. I had also been given the task of finding the graves of the Armenian relatives of my friend in Krasnodar. When I asked him why he didn’t want to visit himself, he told me that after his aunt and cousin were killed by a mine blast during the war, he had lost all interest in revisiting the place where he used to spend his summers as a child.

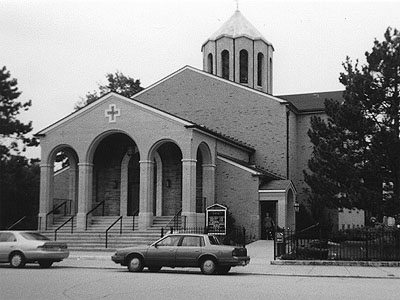

Having previously been the most cosmopolitan city in the North-Eastern Caucasus, Chechnya’s capital Grozny was prosperous and multi-ethnic, but with the onset of war in 1992 the city was destroyed and many fled the republic. The majority of Chechnya’s Christian population left including the approximately 15,000 Armenians that lived there, including my relatives.

“I have lived in Grozny all my life and have never been to this part of town,” Timur laughed as we drove. This is not surprising, considering Timur is Chechen and Muslim. There are four Christian cemeteries in Grozny, and only two Muslim cemeteries; Chechens have a strong tradition of burying their dead in clan cemeteries in their home villages in the mountains and foothills of Chechnya’s south and not in the city proper.

The cemetery, near Grozny’s old cannery, was in bad shape. Only around 20 percent of its large territory is accessible — thick brush has grown over the footpaths making it virtually impossible to get through without a cutting tool. Only a small number of graves look like they are receiving any care. Others still lay on the ground, bearing the scars of rockets and bullets from war.

A clean up of the city’s cemeteries seems inevitable however, given the current Chechen leadership’s penchant for aesthetically improving the city. Virtually no signs of the wars remain in the capital — astonishing, given the massive scale of damage it sustained.

The city’s mayorship has recently announced plans for the conservation of some of Grozny’s older Christian cemeteries, including the one I visited. These plans however pose a problem – conserving a cemetery means no new burials can take place. Those still alive whose family plots are in conserved cemeteries cannot be laid to rest there. Some say that Christian residents should have been consulted before the decision was made to effectively close those cemeteries.

With so few Christians left in the republic to speak out against the policy however, the plan is not likely to face any strong opposition.

I did not find my relatives in the cemetery unfortunately, but I did take photos of as many Armenian graves as I could, hoping to eventually find a connection, both for myself and for my friend.

Karena Avedissian is a doctoral researcher at the University of Birmingham studying social movements in the North Caucasus. She has just completed a stint in Russia interviewing activists in Krasnodar and the Republic of Kabardino-Balkaria.