Meeting in the Middle: Armenian Genocide Thoughts, Part 2

My grandfather died when I was 13. He lived down the street from our house, with my grandmother, among a dozen fruit and flower trees that felt like paradise. If the Garden of Eden did exist, I was sure that it was located in the backyard of my grandparents’ house. He complained of headaches for months, until one day he was diagnosed with a brain tumor and slowly but surely he became a shadow of his former self until the wind swooped him up and carried him away to Armenia.

He flew across the ocean, above Yerevan and went home to Mt. Ararat to rest in peace.

Off to Armenia he went. I know this because my grandfather was a very emotional man. A shoemaker with the most delicate hands you ever laid eyes on, he grew sunflowers and played with prayer beads the color of the Earth. My grandfather, who came to America from Tehran, longed for Armenia. His hazel eyes, shrouded with big framed glasses, would well up every time “Armenia” was mentioned. He could hardly finish telling me a story without being overcome with tears. I don’t think there was a day I saw him without a newspaper, trying to make sense of region that stirred such powerful feelings inside him.

My grandfather cried when you mentioned Armenia, and he cried again for those who lost their lives 95 years ago in the Armenian Genocide.

I cried that I lost him, but I never heard him or my grandmother instill any hatred in me about Turks. In fact, they didn’t speak badly about Turkey, the actually spoke Turkish. Originally from Tabriz, located on the upper most edge of Iran, they lived alongside Armenians, Persians, Azeris, Kurds and most likely Turks.

I never heard the word ‘hate’ from them, nor did I ever hear it from my parents. My paternal grandmother, born in Krasnador, Russia lived among Armenians, Turks, Azeris and Russians.

It wasn’t until I entered the Diasporan Armenian private school system later in my life that I began to see how much hate had been indoctrinated and institutionalized into students’ minds. From walks, to posters to masses to history lessons to videos and lectures and everything else, it was an identity that was being forged almost all the time on 1915. No one ever said “you should hate Turks,” but they didn’t have to. The seeds were already sewn.

I tell you about my grandfather’s story to explain that the heaviness, the pain, the sorrow is not any less in me than it is in an Armenian youth whose nationalism and disdain for Turkey is so strong, that he is blinded by it.

I feel it too.

And while I know that tomorrow, thousands upon thousands of Armenians will invade busy streets in Los Angeles, marching with shirts and signs and anger to the Turkish consulate, there is nothing I would love more than to drive down there myself, part the never ending sea of people with a lot of “pardon me’s” and “excuse me’s” and march right up inside that consulate to sit down and talk with the Turks who work there.

I will not march to demand recognition. I will not now or ever drape my car in red, blue and orange and drive down streets. I will not yell phrases about “dirty Turkey trying to hide the genocide.”

I don’t want a spectacle. I want dialogue.

I am not interested in politics. I’m interested in humans.

And I find it utterly ridiculous to protest so forcefully and so obnoxiously without any real interest in discussions and discovery. I want to ask those protesters, have you ever met a Turk? More importantly, do you have any interest in doing so? The majority would answer, “no.”

And the same question can be asked of Turks. Have you ever met an Armenian? Do you have any interest in doing so? Do you understand the pain, the suffering, the reasons why this continues to torture and haunt Armenians, even 95 years later?

Yesterday a friend alerted me to a column in Today’s Zaman by Orhan Kemal Cengiz that discussed the “pain-body,” a concept developed by Eckhart Tolle.

The more I read about this concept, the more I realized eloquently it expressed the state of the Armenian Diaspora.

“The pain body wants to survive, just like every other entity in existence, and it can only survive if it gets you to unconsciously identify with it. It can then rise up, take you over, “become you,” and live through you. It needs to get its “food” through you. It will feed on any experience that resonates with its own kind of energy, anything that creates further pain in whatever form: anger, destructiveness, hatred, grief, emotional drama, violence, and even illness.”

Once the pain body has taken you over, you want more pain. You become a victim or a perpetrator. You want to inflict pain, or you want to suffer pain, or both. There isn’t really much difference between the two. You are not conscious of this, of course, and will vehemently claim that you do not want pain. But look closely and you will that your thinking and behavior are designed to keep the pain going, for yourself and others.”

This is the description I had never been able to put into words, about not only how, in a short period of time, I was made to feel in school, but how the general Armenian Diaspora feels, and still feels today and how this “pain-body” is eating us alive, stopping progress and change. It’s like having an argument with a family member and not speaking to them for 10 years. You live with that pain inside you, it stews in your insides and creeps in your veins and breeds hate. It does no one any good, not you, not your family member, and suddenly you find yourself having wasted and given up 10 years of love and laughter and companionship and trust all because you couldn’t just sit down together and talk about things.

I don’t want this.

I want to move forward. I want to be at peace.

I do not want a Genocide to define me.

I do not want a “pain-body” to breed fear and hatred in the minds of young boys and girls. I do not want this “pain-body” to encapsulate someone’s mind so entirely, that they feel lost without it.

I want to simply, meet in the middle, because Hrant Dink is gone and there has to be some lesson we have to learn from his death. There has to be some way we can keep building the bridge that he started and not let his exit from this world go in vain.

Another friend, an amazing woman named Nigar from Istanbul told me about commemorations in Turkey happening today. A candlelight vigil will be held in Taksim Square and a documentary called “What Happened in 1915?” will be shown.

The black and gray website announcing the event, with signatures, is simple in its message.

“This is OUR pain,” it reads. “This is a mourning for ALL OF US.”

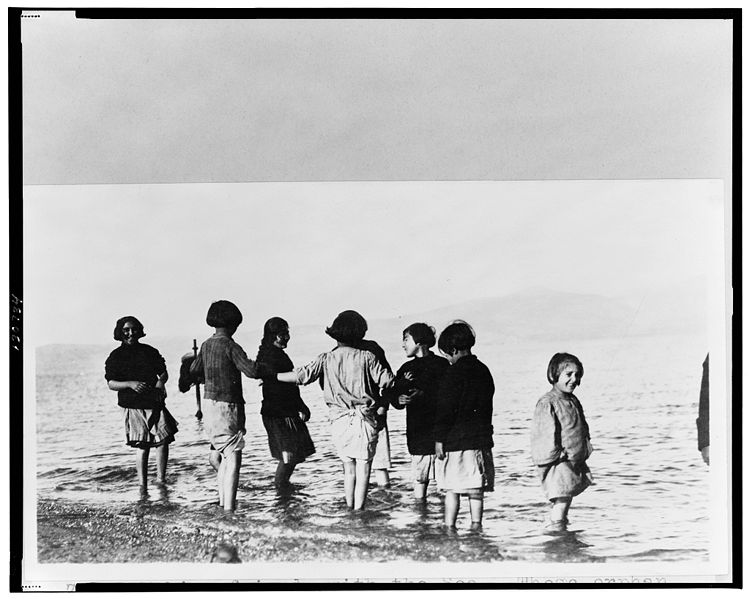

It talks about Armenians who lived in Turkey – the grocer, the goldsmith, the friends and companions.

On April 24th, 1915 they were “rounded up”. We lost them. They are not here anymore. A great majority of them do not exist anymore. Nor do their graveyards. There EXISTS the overwhelming “Great Pain” that was laid upon the qualms of our conscience by the “Great Catastrophe”. It’s getting deeper and deeper for the last 95 years.

We call upon all peoples of Turkey who share this heartfelt pain to commemorate and pay tribute to the victims of 1915. In black, in silence. With candles and flowers…

Are Diaspora Armenians aware of this? Are they able to see a Turk as a human, capable of understanding, willing to converse, and full of empathy? Or is the “Genocide Tunnel Vision” impairing any sort of break in the cycle?

In the essay, “Waiting for Tables,” published in the Brooklyn Rail, author Nancy Agabian touches on this subject. “Perhaps we have become so defined by our loss that we cannot imagine ourselves without it,” she writes. “Getting over this psychic disconnect is comparable to what Turks will have to go through, as a nation, when they admit the genocide and realize the whole of their history so differently. It will cause a great shift in the way that they understand themselves. So we have more in common than we realize: the impossible imagination.”

Yes, perhaps we more in common than we realize, so let’s meet in the middle and talk instead of shout.