Bring Me Some Dirt: An Armenian-American & The Motherland

Have you ever suddenly started thinking about a place—a restaurant let’s say—that no longer exists? Come on; don’t say “Not really.” You know what I’m talking about: you’re just sitting there thinking about work or car upkeep or your kids when out of the blue your head takes you to the Farmer’s Market—which had nothing to do with farmers or markets; it was more like a circular indoor mall with no department stores—over there where Tulare and Divisadero split, and you can see that Mediterranean place, run by Greeks I heard some people say, and they served that chicken and pilaf dish with the weird sauce on it that was made out of madzoon (yogurt) and mayonnaise and the pilaf was yellow and I was drinking regular Pepsi at the time instead of Diet.

I just bring it up as an example of your brain sometimes grabbing the controls and sending off weird memos, saying to your mind—Hey, you used to have lunch over there with Roosevelt teachers, remember? Just sayin’—for no reason and you can smell the chicken and hear teachers laughing sardonically and even taste the Pepsi. Well, maybe that’s what happened that day, like a brain hiccup or something, when I told a student I wanted some brandy.

I wasn’t out to corrupt him or trying to present myself as “cool” for thinking about brandy; it just came out. I was asked what he could bring me for a gift from Mexico when he returned from visiting Grandma during Christmas break, and of course I knew the answer, “Nothing, thanks. Just be sure to have a nice time, and then you can write about it in your journal.”

But instead what came out was the answer that I might have given to an adult, not all of them, just some of them, just to be funny. I panicked for half a second; then I thought about the kid and thought he would be OK with it, that he would know I was kidding even though it was dumb on my part to have said it but like I say, it was that brain thing, you know.

“Ho-ho” the kid said, “OK, Chavoor, I’m a do that.”

He was delighted that I was so real with him, except that it really wasn’t real. I don’t care for brandy, I’m OK with it, don’t have anything too much against it, but it wouldn’t be something I’d order if I wanted something to drink, which I don’t do often and now the kid thought I was revealing my true nature to him, that if I could have him bring anything, it would be a bottle of brandy. In the first place I don’t often have booze in the house—it makes me feel guilty—in the second place if I have something to drink other than a beer it’s either Wild Turkey on the rocks or gin and tonic. I’ve had apricot brandy which sounds better than it tastes. I told the kid I was just kidding, but he didn’t say anything, he just grinned.

When the two week Christmas break ended I had forgotten about the whole thing. A couple more weeks went by and one day after school the kid comes into my room—smiling—with something behind his back.

“Hey man, what’s up?” I said from my desk while we walked in circles with that grin on his face.

“I guts it,” he said like he’s about to signal the revelers to jump out and give me a surprise birthday party.

“Got what?” I said, eyeing him a little cautiously.

Instead of answering he rushed toward my desk and slammed a large bottle of El President Brandy in front of me.

“What the hell are you doing?” I shouted jumping up from my desk chair.

“You said you wanted some brandy!” he laughed, not in the least hurt at my reaction.

“You…I…put it away!”

“It’s cool, Chavoor,” he said and he put it inside his overcoat. He was still smiling, quite pleased with himself.

“I said I was kidding OK? When I said that.”

“It’s for you, Chavoor. Merry Christmas.”

He had instantaneously changed from a lively, spirited mirthfulness in his tone to a deep, almost somber sincerity as teenagers can do.

“I can’t accept this,” I said while at the same time remembering the crestfallen look on a girl named Adelle from my first English class at Roosevelt, when she tried to give me a gigantic heart-shaped box of chocolates for Valentine’s Day that I declined to accept. Wasn’t this situation just as bad? Worse, maybe.

“Come on, Chavoor,” the kid said, “I been hiding it under my bed for like a month.”

“You brought this to school, man. I can’t believe it. What were you thinking?”

“All right. Don’t worry, Chavoor. I got you.”

He nodded and left the room with the bottle securely hidden in his overcoat.A week later he showed up on a Saturday on my front porch.

“We ain’t in school now,” he said proffering the troublesome gift.

“OK,” I said, touched and worn out by his persistence, “thanks.” He hopped off the porch and skipped to his car.

It’s risky to ask someone what he wants when you’re going somewhere on vacation. I don’t think I’ve ever done it before. Well, not because it’s risky but it never occurred to me. The question can sound like, “Hey, I’m going on vacation and you’re not. Can I get you some useless trinket to remind you?” It’s not fair though to attribute all such offers to boorishness.

I’m sure that for some, or OK, for many the offer is sincerely made or it’s one of those empty expressions that we say automatically like “How are you feeling today?” to which you are expected to equally automatically respond, “Fine, thanks,” as opposed to “I’ve been a little gassy lately.” And if that’s true then the answer to the “Can I get you something?” Should be “No, thanks. Just have a great time,” which would have saved me a lot of trouble with the kid and the brandy, but on the other hand would have meant I wouldn’t have gotten a bag of dirt from Ed Barton when he asked “What can I get you?” and that would have been an incontrovertible loss.

Ed Barton is one of the good guys. He is a calm, wise follower of God. He has many insights and a sense of humor. He is also a sincere man and a man of his word. He’s also the only Armenian I know whose voice has that homey, soft spoken, nasally, Midwestern tone very much like Jimmy Stewart.

Ed and I along with Tom, Tedd, and Al—a recreational therapist, a minister and a principal, respectively—have been meeting for breakfast once a month for almost 30 years now. Ed and I also taught at Roosevelt and we all attended the same church. The breakfast club was in session one morning and Ed told us he was going to Armenia.

“Armenia, huh?” I said, “Wow, that’s really cool. I always wanted to go to Armenia, you know, get back to the roots and all that.”

“Roots, uh-huh, that’s good. You’ll go one day,” he said in his gentle voice.

“Yeah, maybe.”

“Tell you what, I’ll get you something. What can I get you?”

“Bring me some dirt from the Motherland.”

I was surprised at myself; it wasn’t like me to assign meaning to inanimate objects. There were so many normal requests to make—a cross, a picture of Mount Ararat, and yes even Apricot Brandy—and I tell him dirt. But I meant it, I wanted dirt from Armenia. If I could go to the Motherland, the Motherland could come to me.

“All right,” he said, his eyes sparkling, “I will. I’ll do that.”

“And I’ll plant a fruit tree and put some of it there.”

“You bet. That’s it.”

I never doubted that he would tote dirt 6,000 miles in his suitcase. When Ed returned and we were all at breakfast again we asked him about his trip.

“It was fantastic, a real blessing. Every Armenian-American should go.”

“What was the best part?” I asked.

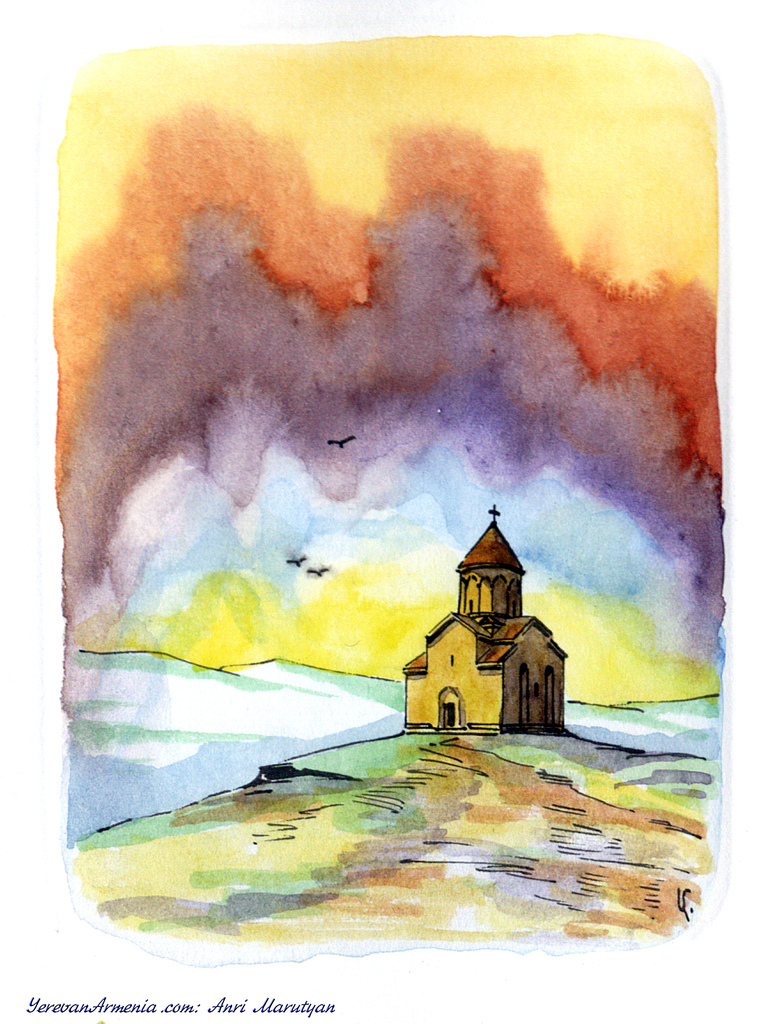

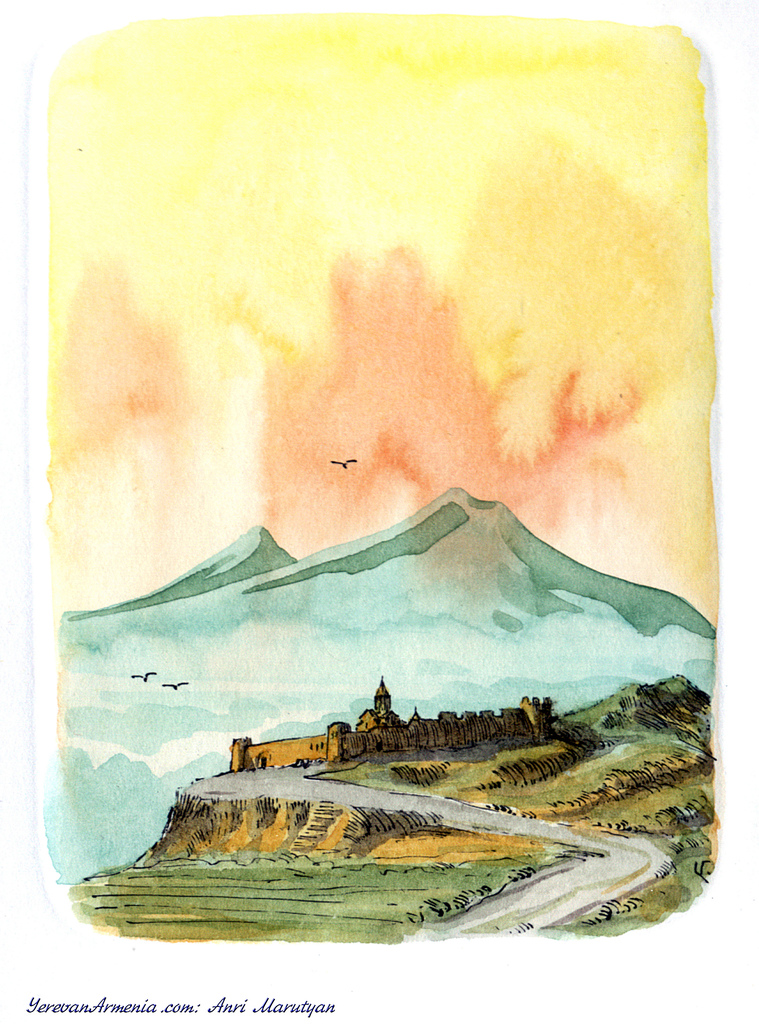

“I’ll tell you what, when I first saw Mt. Ararat my heart did flip-flops. I experienced a deep sense of connection.”

“Wow,” Tom said.

“I had seen pictures of it for many, many years…” Ed continued.

“We all have,” Tedd interjected.

“But when I saw the real thing, the symbol of Armenia, I was really moved.”

“Cool,” I said.

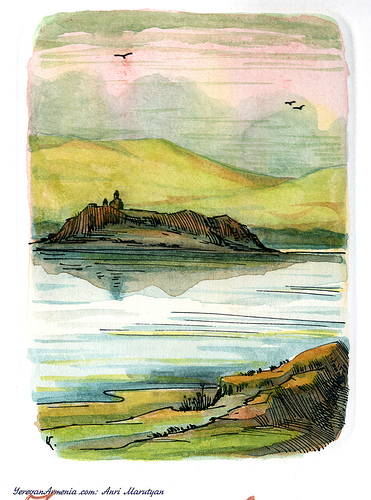

“A few days later I got a closer look at Ararat as we were visiting one of the churches high up on a mountain. We were about two miles east of the Turkish border, the Arax River ran below us. I saw Ararat, about 40 miles to the west, and I had a different kind of emotion.”

“What was it?” Al asked.

“When I saw Ararat, our national symbol, inside Turkish territory, that really belonged in Armenia, well it gave me a sadness that was real hard to deal with.”

“A sense of loss,” I said.

“Yeah. But still mixed in with this inspiring power though,” Ed murmured. We sat in reflective silence.

After breakfast, out in the parking lot Ed handed me the gift. When I got it—doubled bagged in plastic—I thanked him again and again. When I held the bag I thought I felt something, like a vibration in my soul. I put it in the passenger seat up front in the Camry and at stops I would turn and look at it, and if I had time, if the red light was long enough, I’d put my hand on the bag and feel that feeling, humming of the soul. I don’t know, I can’t explain it. I brought it home and put it in an old gym bag in the bedroom closet and every time I went to pick out a shirt for the day, I got that same feeling.

Now the freshman football team that year was, well, they were horrible. But they weren’t as awful as the ‘95 team the year before it. The 1996 edition of frosh football opened with an away game against Sierra High School and we actually had a chance to win—something the ’95 team never came close to experiencing—but in the end we dropped two passes that would have been touchdowns and then a kickoff return for a touchdown got called back because of a penalty.

We lost, 14-12 which was better than the shellackings we took in ’95 against the same team, but I knew that “had a chance” and “would have been” wasn’t going to do us any good. We had John Romero a compact, solidly built linebacker who loved hitting people. We had to win some games to give the rest of the kids some confidence. Our next game was another road trip, versus Yosemite High. It was time to change the luck.

There is a lot of superstition in football and sports in general I suppose; if faithful consistency doesn’t get results you have to switch things around, do things in opposite order or manner. This is called changing the luck. It’s one of those things you do whether you believe it or not because if you say you don’t believe in it and don’t do it, chances are more than good you’ll end up jinxing yourself. So instead of wearing a suit and tie to school on game day I switched to the shorts and shirt that I wore while I coached. I yelled at the kids I coaxed and coaxed the kids I yelled at. I put two quarters and two pennies in the coin holder in my car, 52 cents, my jersey number from high school. Up until that week, Coach Canales and I didn’t leave campus at lunch on game day, but to change the luck we went to Javier’s, the local Mexican restaurant, ate like kings and felt good.

But I wasn’t taking any chances; I had to bring the dirt with me.

I had the gym bag between my feet on the floor of the bus where I sat. When I reached down and touched the bag that held the dirt of the Motherland, my soul stirred. I kept reaching down to touch the bag to see if I would feel the same surge, and I did. Finally I picked up the gym bag and plopped it in my lap.

“What you got, Coach?” Canales asked, looking at my ratty old gym bag through his Ray-Bans.

“Inside here, right inside this plastic bag? I got dirt.”

“Dirt?” he laughed.

“From Armenia.”

“Yeah?”

“When I touch the dirt, I feel the power. The ancestors are with us.”

I wasn’t about to back pedal. I wasn’t going to jinx myself, the kids or the game.

“Excellent.”

“Yeah, and that’s not all.”

“What else?”

“We just rolled through Oakhurst where Grace and I first met 20 years ago.”

“Good omen.”

“Damn straight.”

Dirt from the Motherland while passing the spot where I first met my beautiful Armenian bride—we couldn’t go wrong.

We led 13-0 at halftime but I was nervous. The offense only scored one touchdown; the other was on a kickoff return. Not much to brag about but at least we had the lead. While Canales gave the halftime speech I reached into the gym bag, worked my way through the plastic bag and submerged my hand in Armenian soil.

In the second half the offense went into a scoring frenzy and scored five touchdowns. Everyone got to play, even the third stringers who had no idea what they were doing. With 10 second left the score stood at 46-0 and we all chanted the countdown loud, proud and crazy. We didn’t calm them down; we let them celebrate and savor the moment. It was a raucous ride home. The kids whooped, hollered, whistled, and sang “Got that Rider spirit down in my heart,” that Canales swiped from Fresno State who swiped it from every church summer camp in America who ever sang “Got that joy, joy, joy, joy down in my heart.”

When the bus roared up Tulare Avenue and then pulled into the Roosevelt parking lot where family and friends waited, the cheering inside and out the bus exploded. It was so joyous that even the bus driver joined in on it.

The Yosemite football program was in its second year of existence. They were predominantly skinny white kids who seemed afraid of kids from an inner city school. They had no speed and limited talent at the skill positions. They were one of the two teams that we beat the year before. Did any of that have anything to do with the most lopsided victory in the four years I coached? Of course not. Don’t be ridiculous! It was the earth of the motherland, the presence of my Armenian ancestors that stirred my soul and apparently stirred the souls of our kids that day.

So sometimes—not every time—we stand to gain when we blurt out impulsive answers to ordinary inquires. Makes for a good story, anyway. And if you don’t believe it, you’d better watch out; you might just end up jinxing yourself.