Letter From the Editor: The Stinging Motherland

“The motherland should be best loved from afar,” a man said to me the other day, “or else it will sting you.”

This man, whose first name I never received, came to Los Angeles in the early 90s from Armenia, and after several years of living in Hollywood, where the palm trees sway in the breeze and at least a handful of ethnic groups can be found in just a few blocks, he made up his mind to go back.

He only lasted one year.

Fond of striped polo shirts and buying produce from Armenian owned-vans that loudly announce their presence with a clown-like horn, his face drips of remnants from another world that he’s chosen to leave behind.

There’s nothing in Armenia, he tells me, his eyes filled with despair.

I tell him I’ve never been, that I want to go.

Why he asks. “Why would you want to go?”

I could have told him a thousand reasons why, but it was starting to drizzle and I didn’t have an umbrella, so I told him I wanted to go and write.

“There’s nothing to write,” he told me.

It was a sad moment. Here was a man who was hopeless about a place he called home, and there wasn’t much I could say to convince him otherwise. He isn’t rich, he doesn’t have a house in the hills and a car worth more than most people’s salaries. He takes his dog out for a walk most days, chats with other Armenian ex-patriots who constantly rustle prayer beads between their hands on the street corners in Hollywood and returns home to his apartment, to his wife and daughter and son, and repeats the process all over again the next day.

I couldn’t stop thinking about his characterization of Armenia. If you get too close, you’ll get stung.

A few days after, I got a few stings of my own. Two new readers accused this site of receiving funding from a “Turkish-American think tank organization,” and told others to “follow the money on this site.”

Another called me a “fem-nazi” and seemed to have a problem with me talking about well, problems in Armenian culture. Then I got several emails that outlined how I was a fake Armenian because I purchased Kurdish music. Real Armenians don’t need to listen to the music of the enemy, I was told. Real Armenians don’t come from Tehran.

And just when I thought it was over, a young man from Australia sent me an angry message.

“Don’t you know you’re burning the name of Armenians?”

“Why? What did I do?”

My crime? I had written I suppose, that Armenian girls liked to have sex.

Armenian girls don’t have sex, at least not outside America! Didn’t I know?

I guess I didn’t. I told him I would research and write an article about this. I still intend to.

I kept going over these comments in my head and remembering what my new friend had said to me.

“The motherland should be best loved from afar, or else it will sting you.”

Well, it wasn’t the motherland, but her children that left a bad taste in my mouth. It wasn’t the act of criticism that stung, but the scope of it.

And after a few weeks of contemplation, the only appropriate response I could come up with was none.

There is no appropriate response to absurd accusations about American-Turkish funding when you lose money every month pouring your energy and time into keeping this site operating. There is no appropriate response to archaic ideas that ethnicity and genes automatically voids Armenian human beings of having any sexual desires (and expressing them) whatsoever.

There is no appropriate response to the idea that I am somehow less of an Armenian because my background finds roots in another country. And to those who think that there is nothing that “ails us in our culture,” you’re looking through a veil of ignorance, because there are issues worth discussing no matter what background you come from. To those that think I go on about women’s issues unnecessarily, all of them who are men, that’s due to the fact that many rarely do in the context of the cultures of the South Caucasus.

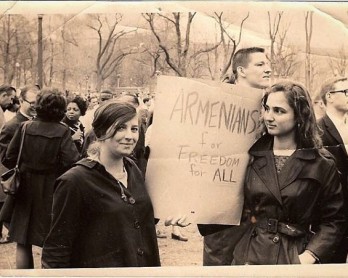

There are issues and ideas outside of the Armenian Genocide worth discussing. There is always more to the story than a black and white chess board with kings and queens on each side that seek to come out on top. Armenians live in a polarized world. You’re either with us or against us. You are either a Christian-loving, Turkey-hating, fighter for Genocide recognition or you’re the enemy. There is no room for discussion, for other view points, for self-reflection.

I think there’s room for everyone. I think that’s the only way to real change and progress. The world, its people, and Armenians are more complex than that. They deserve more, and there’s an entire segment of people who are ready and willing to provide that discourse.

“The motherland should be best loved from afar, or else it will sting you.”

That’s OK. I can take a stinging now and again.

There is no American-Turkish lobby funding this site. There is me, doing what I can after hours, along with a few passionate contributors, to produce articles, posts, photos and more that can add to an increasingly global discussion. There is no money being made, although that would be nice – only ideas. There are issues that will be discussed, pertaining to women or otherwise, no matter how badly some either think they don’t exist or are embarrassing because that’s what journalism is about. And yes, I will eat my ghormeh sabzi, listen to Kurdish music, enjoy Lebanese food with Turkish and Jewish friends – none of which make me less of an Armenian – and still look forward to the overwhelming emotion I will feel when I step foot in Armenia.

The man who left Armenia still longs for it. If you look beyond the despair in his coffee-colored eyes, you’ll notice. He drives an old beige car and excitedly picks up his ringing cell phone that’s hoisted to his belt. His father was from Cyprus, he practically knows all the Armenian families who live there. He lives above another Armenian family whose Russian-Armenian discourse can be heard down the street.

“There’s nothing left in Armenia,” he says, shaking his head. “It’s a hard life.”

I look down, because I don’t know what else to do. I want to know more. More about his life many years ago, about his experiences between two sister cities that sometimes feel so alike, but we go our separate ways – him to meet his friends, a group of Armenian men with such descriptive faces, in track suit bottoms and polo shirts, that you find it hard to look away. Me to chase another story and a landlocked country thousands of miles away on my mind.

“The motherland should be best loved from afar, or else it will sting you.”

Maybe, but it’s worth the risk.