Op-Ed: Deciphering Armenian Narratives in History, Film

I have read many books about the third generation discovering stories of genocide in their family to find myself angry, frustrated and wanting nothing to do with the people this history is speaking of. But I knew I had to watch “My Grandmother’s Tattoos” because it was exposing the often unknown story of women who survived, women with tattooed faces whose portraits I had seen in passing, women whose stories do not exist outside of their own heads or graves. Watching this film, I was hoping to find a changed narrative, one that would tell the story differently, a story without a victim and without an enemy. Perhaps I was even hoping to be convinced that, on the contrary to what most Diaspora Armenians advocate for, in fact there was no “Genocide”, and that, much to the satisfaction of Turkey’s nationalistic propaganda, the 1.5 million Armenians who perished in the early part of the 20th century was all a lie.

The film did neither of these. Instead, it was a story I had heard of before about Armenian women being taken as wives and concubines into Kurdish and Turkish households. But much in the same way that the director of the film suddenly realizes that this story is actually about her own grandmother, so does the viewer begin to find herself involved in a particular story that destroys the distance between the past and the present, the foreign and the familiar.

Suzanne Khardalian takes us on a journey into the grave-sites and literally shows us the bones of the perished in the deserts of Syria, particularly in Margadeh. In an attempt to put together the pieces, the fragmented stories of how her grandmother arrived in Syria become indicators of the sexual harassment, rape and abuse she was subject to as a refugee. As always, the burden of war, genocide and violence falls on the shoulders of the women as they have to endure surviving even after having already survived. What is left after the erasure of this history is a deeper, internalized shame that continues to live in women’s bodies for generations after their foremothers were raped and forced to become wives of men they would otherwise not choose to marry.

Interestingly, this film came about at a time when the French Genocide Bill criminalizing the denial of any recognized genocide, including the Armenian genocide, was passed in France. As someone who believes in free speech, I stand with those who oppose this law as one that is racist, with a particular aim to criminalize the Turkish communities who live in France and who may not always be aware of this particular history of their home-country. We must recognize first and foremost the politics behind France as a Western power involved in the “war against terrorism”. And for Armenians who grew up being told of the bad things the Turks did to us, learning to associate Turkish people with Islam, we must become better aware of the strategies used to separate the so called good Christians from the so called bad Muslims as it plays out in the West.

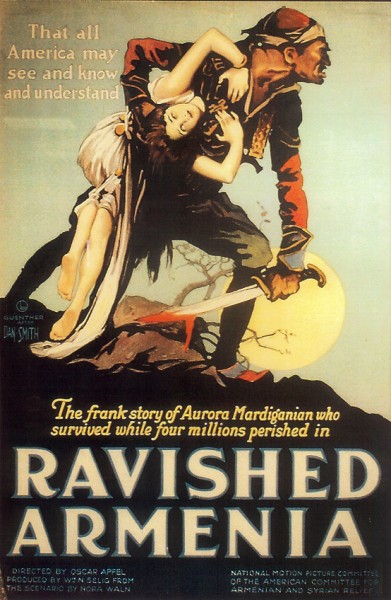

In 1919, when “Ravished Armenia,” a film about the experiences of an Armenian woman during the genocide was released in the U.S., the poster advertising the film depicted an overly masculine man with dark skin, holding a young, very thin and very pale woman under one arm, while also holding a bloody sword in the other hand. The poster read: “The frank story of Aurora Mardiganian who survived while four millions perished in Ravished Armenia.” Besides exaggerating the number of deaths, the text sensationalized the survival story of one woman during a time in the United States when the expression “starving Armenians” was commonly used to coax children to eat all of the food on their plates. Furthermore, the image appropriated the history of the Armenian genocide to fit the racist narrative of the West.

In 1919, when “Ravished Armenia,” a film about the experiences of an Armenian woman during the genocide was released in the U.S., the poster advertising the film depicted an overly masculine man with dark skin, holding a young, very thin and very pale woman under one arm, while also holding a bloody sword in the other hand. The poster read: “The frank story of Aurora Mardiganian who survived while four millions perished in Ravished Armenia.” Besides exaggerating the number of deaths, the text sensationalized the survival story of one woman during a time in the United States when the expression “starving Armenians” was commonly used to coax children to eat all of the food on their plates. Furthermore, the image appropriated the history of the Armenian genocide to fit the racist narrative of the West.

A large portion of Armenians I have come into contact with both in Armenia and the Diaspora accept this narrative. They believe that somehow the oppression of the ethnic group that has historically oppressed us will cancel our oppression, that by dictating people to recognize the Armenian Genocide we will suddenly find ourselves living in a more just world. What we don’t realize is that we are merely a tool used to further more powerful countries’ narratives of oppression and socio-economic interests.

“My Grandmother’s Tattoos” is not attempting to advocate for such racism and discrimination. But in the minds of less conscious viewers, the lines between Turkish and Kurdish may become interchangeable, as the majority of both practice Islam and both are associated with the state of Turkey then and now. Therefore, we must always be mindful of how the story is presented, especially when taking into consideration that many of the viewers are Diaspora Armenians who often believe in the idea of an enemy, reunification of historic lands, and war as the rightful method of protecting and obtaining those borders.

The film ends with the beautiful mountains and apricot filled trees of Armenia where the filmmaker and her family are enjoying a feast. Khardalian confides in her audience that this is where she feels most at home, that she feels in Armenia as she’s never felt before anywhere else, and that this land belongs to her. She refers to Armenia as a paradise.

As someone who emigrated from Armenia with her family 15 years ago, I am well aware of the different issues that plagued Armenia then. And as someone with deep ties to many of the Armenian citizens who still live and struggle in Armenia, I can attest to the fact that this land, with all of its beauty, power and allure is the opposite of paradise to many who do not always have the choice or the option to reside elsewhere. As much as Kharadalian has a right to feel at home in Armenia and truly feel herself in paradise there, so do all of Armenia’s citizens have the right to feel at home and find a little bit of that same paradise on that very same land.

I believe that “My Grandmother’s Tattoos” will only be the beginning of an attempt to expose the unknown histories of ethnic/historic Armenians, Armenian citizens, Kurds, Turkish people, Assyrians, Greeks, Lebanese, as well as the many other peoples of our shared world. And I truly hope that through this gained knowledge we will be better equipped to deal with one another’s differences in order to make space for all citizens of the world to live in peace, including Armenians and Turks.

Maral is a passionate artist and writer who is in the throes of creating a world in which she and others like herself can live in peace and abundance. When she is in love she believes that this is more and more possible. She is currently attempting to find a room of her own in which to write and complete a memoir/poetry book. Check out her blog at http://www.maralbavakan.blogspot.com