Sitting Still: Reflections on Armenian Portrait Photography

It was in 2008 that I first came across a catalogue titled Mapping Sitting: On Portraiture and Photography by artists Walid Raad and Akram Zaatari. The project brought together different kinds of portraits from the Arab Image Foundation’s archive taken in the Middle East during the mid-20th century. Portrait studio photography is deeply satisfying to my visual sensibility and to my practice in regards to social and cultural constructs. My family is from the Middle East and I grew up understanding my lineage through studio photographs in the same style from the same era.

Page after page, I looked at pictures of people I didn’t know that I instantly recognized. Could that be my great uncle as a young man standing in the square in Tripoli? Is that my grandmother’s Syrian neighbor who now lives in Anaheim? Weren’t those my aunt’s two thick long blurry braids in the background? I flipped through the pages voraciously; it was so much of what I wanted to see in one place.

Slides and film from portrait photographer Edward Tatoulian’s shop./Photo by Gilda Davidian

Mapping Sitting is organized in sections including passport photos, semi-candid shots in public spaces, and group portraits. Some of the pictures bleed from the edges of the page, creating a sense of continuity similar to that of looking at a roll of film. Though the organizational methods are distinct, the combination of faces and places is by chance. In some sections the albums that contain the images are also included, creating a papery context with a tangible smell of times past. In others, a faded collage of images background the photograph, framing it like a sharp detail in an otherwise faded memory. Each section is considered carefully, creating a map that is both as arbitrary and meaningful as the way constellations are drawn together.

During that same year, I began working on a series documenting Armenian photographers in their portrait studios throughout Los Angeles. The project started after visiting a friend at her grandfather’s studio, Photo Aram, in Glendale, Calif. The space was an incarnation of the Beirut I envisioned when my parents talked about their life there. I decided to find more portrait studios like it to document at a time when photographic practices were rapidly changing in the transition from analog to digital. During my research, I discovered that studio portraiture has been an interwoven part of Armenian culture since the beginning of photography. As religious minorities, Christian Armenians were among the first photographers in the Ottoman Empire since Muslims could not practice photography. After the Armenian Genocide in the first part of the 20th century, survivors took the trade with them where they went – to Israel, Syria, Lebanon, and beyond.

Edward Tatoulian moved his photography studio from Lebanon to Los Angeles during the Lebanese Civil War./Photo by Gilda Davidian

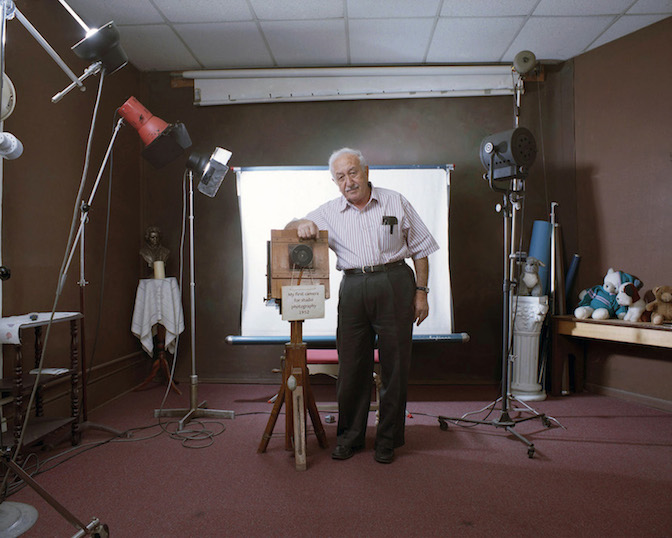

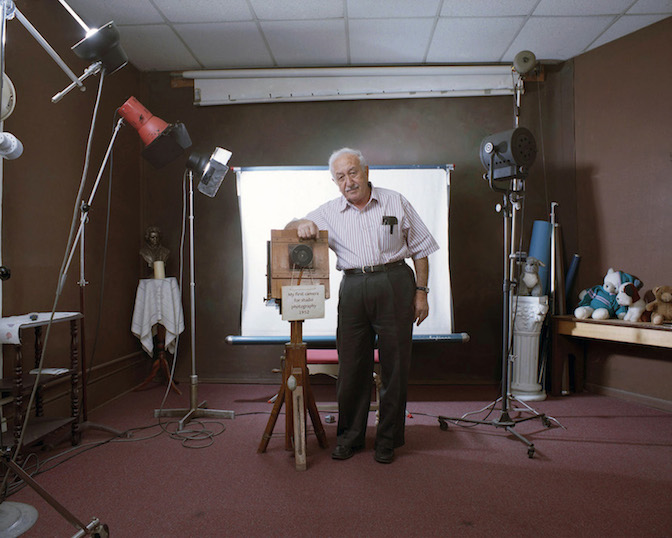

While working on this series, I befriended an Armenian photographer in his mid-80s named Edward Tatoulian who has a portrait studio called EdoArt at the corner of Hill and Washington in Pasadena. Edo moved his practice from Lebanon in 1976 during the civil war in Beirut. He had a special box constructed for his 4×5 camera that was made by woodworkers in Haleb. He was a gifted retoucher trained in Tripoli by his brother-in-law, photographer Antranik Anouchian. His studio in Pasadena was immaculate, and though his once active practice had been whittled down to the occasional passport photo, he was prepared for a full portrait shoot at a moment’s notice. The objects he had in his studio included a column, a candle, a bronze bust of Beethoven, stuffed animals, a variety of hair combs, and some makeup. I photographed Edo standing next to his first camera, a beautiful handcrafted 8×10. I framed the photo and handed it to him nervously. He asked, “Did you take this or did I?”

Over the years, I have continued to visit Edo’s studio to chat about photography and the old world. During one such visit, Edo’s daughter handed me a box of dusty negatives, and so I began digitizing his archive of negatives from his studio practice in Lebanon. Many of the images could be in Mapping Sitting. Scan after scan, I sifted through the faces and wondered about those who sat to have their portrait taken. What were they thinking? Who were they thinking of? I reflected on the stillness of standing in a room in front of someone behind a camera to have your countenance stamped by time. I remember the things I learned while being photographed by my family through the years: If you’re standing next to a plant when you’re being photographed, hold that plant. If you’re sitting, fold your hands in your lap. It’s ok to look off into the distance and to think of another place. Smile or don’t smile.

Edward Tatoulian’s photography studio is a portal into Armenian portrait photographer history./Photo by Gilda Davidian

I took Mapping Sitting to Edo’s studio and we looked through it together. His brother-in-law, Antranik, is featured extensively throughout the book and 3,600 passport photos taken by him were included the Mapping Sitting exhibition. Edo told me how he moved to Tripoli to work for Antranik’s studio when he was 17 years old. He described the place they lunched together with detailed descriptions of the tablecloths, the meals they shared, and the women who worked there. His descriptions stayed in my mind as if I had seen a photograph. I find a picture of Antranik in Edo’s archive that was taken on a trip to Baalbek. Antranik is standing on a rock, dressed in trousers, button-down shirt, tie and cardigan, looking through binoculars. He has one hand in the air, semi-pointing, semi-floating. He is perfectly framed, backgrounded by a stone structure like a giant gazebo. I can’t stop looking at the photograph. I wish I was there. I look through more negatives and I am there. I taste the air at Baalbek, I feel the grandness of the stones. I think about photographing a place where scale is determined by the height of history incarnate as the remnant of a lost place.

Gilda Davidian is a photographer based in Los Angeles whose work on Armenian-American identity has previously appeared on Ianyan. Find more of her projects and photography at her website.