City of Dust: How an Ongoing Construction Boom Is Destroying Yerevan’s Architectural Heritage

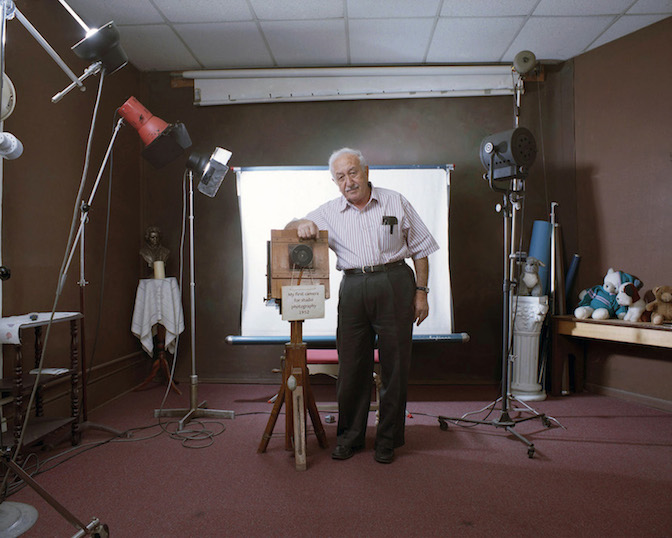

A man walks in Kond, the only historical district left in Armenia’s capital, Yerevan/ © K. Shamlian

One stifling summer afternoon last year in Kond, the sole historic district left in Armenia’s capital Yerevan, a group of men tending to a neighbor’s garden took a break as the sun began its descent, and pointed towards the sky.

“Our Republic Square has a beautiful clock,” one said before going down a set of steep, old, concrete block stairs. “We used to be able to see it. Not anymore.”

The view from Kond, an intricate series of haphazard alleyways and dilapidated multi-material housing structures from as far back as the 16th century which have been left to deteriorate thanks to poor city management, is now blighted by luxury hotels, restaurants and office spaces rising to heights this city has never before seen. The “Pink City,” so named for its use of salmon-colored tufa limestone has a skyline perpetually peppered with cranes, received not one but two inaugural, towering shopping malls recently and has a particularly high dust load that residents combat on a daily basis.

The noise of construction crews have become the soundtrack of a very hot Yerevan summer.

Yerevan’s facade has consistently been reconstructed and shaped with every foreign invasion and political change – from its days being tossed between Persian and Ottoman control, to the drawing of the first city plan in 1924 after Armenia’s entry into the Soviet Union by famed architect Alexander Tamanyan whose basalt and granite statue towers over the city in the direction of Mt. Ararat.

Rapid urbanization in the 1960s and 70s impacted Yerevan immensely. But thanks to Post-Soviet modernization and more than a decade long construction boom that contributed widely to Armenia’s double digit economic growth after the fall of the USSR, Yerevan is undergoing a dramatic change once again.

The realization that the city’s latest stage of massive development has come at a tragic cost is now seeping deeper into public consciousness, too: 29 years older than Rome and once considered a crowning glory of Soviet architecture, Yerevan’s “elite,” look – a word often used to describe contemporary yet often charmless architecture built by wealthy businessmen, has risen to tower over the now privatized Soviet social housing buildings and replaced many parts of its layered, intricate architectural history.

Its new, shiny skin has left virtually no tangible relics or connection to its past. Yerevan, many fear, is destined to become a city without a memory.

Construction sites dominate Yerevan’s skyline/ © K. Shamlian

While some 30 to 40 cultural and historical monuments have been destroyed in the last decade, the most recent structure to fall victim to rapid urbanization is a 130-year-old ornate and detailed building known as The Afrikyan Club House, which belonged to the Armenian merchant Armen Afrikyan. The 19th century building – one of the last remaining historical structures from that era in Yerevan – once served as a meeting place for the cultural and political visionaries of the city, host to artists and entrepreneurs who would gather to meet, talk politics and exchange ideas.

The building was purchased by a company called Millennium Construction, with intention to demolish it and build a hotel in its place. But that did not sit well with hundreds of activists who waged a battle with the city’s municipality for the last two years as Armenia’s youth protest culture, aided by social media, has grown considerably.

The fight came to a head when near daily protests took place throughout June and July near aluminum accordion barriers that went up in front of the building and were soon tagged with a litany of protest slogans and nostalgic sentiments. Anarchist symbols and phrases like “The Place of Memory,” and “You Can’t Replace Me” were added across the silver hoarding as protesters – some of whom scaled the building – were assaulted and arrested by police. As activists continuously gathered to bang on the barriers, Raffi Hovannissian, the first Foreign Minister of Armenia and a candidate in last year’s presidential election who launched a protest movement after his failed presidency bid, joined them – telling local reporters that he regretted that Armenia had the kind of authorities who destroy historical monuments.

The “Let’s Save the Afrikyan Club Building” initiative published an open letter demanding the halt of illegal construction. “We call our city “A Museum under an Open Sky Older than Rome,” meanwhile we are violating and destroying our history under that same open sky,” they wrote.

At the time, activists said that according to stipulations in the Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe, ratified by the National Assembly of Armenia in 2008, the destruction of the Afrikyan building and others around the city is simply illegal, as the document’s stipulations outweigh even Armenian governmental decrees.

“This is the first time we are sure that legally, we are quite strong to stop this process,” said Sarhat Petrosyan founder of Yerevan-based architecture firm Urban Lab who has been involved in the protection of historical monuments for over a decade and filed a court order to stop the destruction of the Afrikyan building. “If we lose this structure but we win in court, it means we won’t let any other displacements occur in Yerevan.”

The government, for its part, has promised to relocate the facade of the Afrikyan building and other dismantled historical structures together in order to create an “Old Yerevan,” in one area of the city, but the plan has stalled, leaving the structures permanently dismantled and some of Yerevan’s residents even more disillusioned.

A statue of Communist Revolutionary Stepan Shahumyan, erected in 1931 stands near the Yerevan Elite Plaza, opened in 2013 and said to be the biggest business center in the Caucasus. Meanwhile, the city’s facelift, “Building New by Preserving Old,” continues/ © K.Shamlian

“The policy [in Armenia] towards the urban past, the physical past is so impotent,” said Alen Amirkhanian, an urban planner who teaches at the American University of Armenia. “This whole idea that you can kind of take apart and put back together – that somehow you’re preserving – that’s also a very Disneyland-esque approach to history.”

The country’s urbanization plan has also revealed wide reaching endemic issues tarnishing Armenia’s bid for democracy, more than 20 years after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Through “eminent domain,” city officials have sold off property to buyers which include an oligarchic class that rose to power during the early years of Armenia’s Post-Soviet Independence who have in effect turned the city into their own personal playground. A 2011 Wikileaks cable titled “Tycoons Reloaded: Who Controls What in Armenia,” revealed the extent to which the South Caucasus country’s oligarchs dominate entire industries, including construction and business ownership. According to a recent World Bank report, Armenia was named as having the most monopolized economy in the Post-Soviet Space.

Thanks to a ratification discrepancy, Armenia’s list of historical and cultural monument sites had no protection for five years from 1999 to 2004, a period during which major construction projects either began or land was inevitably sold off for future developments, with no public knowledge or consent.

Sona Ayvazyan, deputy of the Armenian branch of the non-governmental corruption watchdog group Transparency International, says the destruction of architectural heritage came as a side effect of profitable business ventures centered among the country’s elite.

“It’s a targeted approach to earn money by high level officials,” she said. “Construction is usually being done in areas which is profitable, like the center of Yerevan, so that’s how this area became the focus of business men and means for earning money.”

Other recent controversial construction projects include the destruction of the “Pak Shuka” or “Closed Market,” an intricate Soviet-era stone building which housed the city’s most popular indoor fruit and vegetable market. It was partially destroyed and then turned into a modern shopping complex by owner Samvel Alexanyan, one of the richest men in Armenia who also doubles as a member of parliament.

The development of Northern Ave., Yerevan’s main pedestrian boulevard lined with expensive apartment buildings which now sit empty as the city’s poverty rate stands at around 25 percent, was mired with scandals involving property rights issues, where thousands were evicted from their homes. Some residents took their cases to the European Court of Human Rights and won.

In a scathing report released in July, HETQ, Armenia’s investigative journalism outlet, traced the demolition of the Afrikyan Building back to business ventures involving Gagik Khachatryan, Armenia’s Minister of Finance.

As the Afrikyan building was bulldozed, Yerevan activists screened a documentary about the city’s chief architect Alexander Tasmanian on what was left of the structure/ © K. Shamlian

Despite the unprecedented long-term protests and legal filing to stop its destruction, the fate of the Afrikyan building was sealed from the start. For weeks, construction workers took one row of bricks a day as red beret-wearing policeman stood watch, usually when protests had subsided. In late July, a bulldozer finally demolished much of what was left of house, taking with it another piece of Armenian cultural riches.

This month, it was announced that an upscale Raddison hotel will be coming to Yerevan scheduled to open in early 2016. This is in addition to two other new hotels, worth $8 and $50 million respectively, an Armenian news agency reported. The buildings slated to be turned into the hotels need serious reconstruction to “match the current architectural image of the city,” Yerevan mayor Taron Margaryan has said.

Yerevan residents who live in the residential building are now facing eviction.

“Residents woke up one day to learn that the basement of their building where their childhood passed and where their parents lived will become a hotel, because some organization wanted it to become a hotel,” says Sedrak Baghdasaryan, head of the Victims of State Needs NGO, reported ArmeniaNow.

The view from Kond, Yerevan’s last historical district/ © K. Shamlian

Officials are looking to do even more revamping, with the help of international investors.

Last weekend, the city hosted a trade fair called the “Caucasus: Construction and Repair Expo 2015,” in an effort to attract foreign investments in the construction industry.

Always in flux, Yerevan is in the process of redefining itself yet again, exiling its past to history books and Facebook pages that lament the loss with vintage photos and side by side comparisons of what was and what is.

With a diaspora spread across the globe due to an Ottoman-era genocide, Armenians are used to geographic, tangible loss. Many who live in Armenia however, did not suspect that the longing for some kind of permanence would be taking place in their own country.

As the Afrikyan Building took its final breaths, a large, looming thunder and lightening storm descended on Yerevan in the middle of Summer, whipping dust, rain and hail between the city’s skyscrapers.

An apocalyptic warning perhaps, from the ghosts of Yerevan’s destroyed architectural past now stuck in some kind of strange, hovering purgatory.