Pineapples & Lezhankas: Memories of my Grandmother

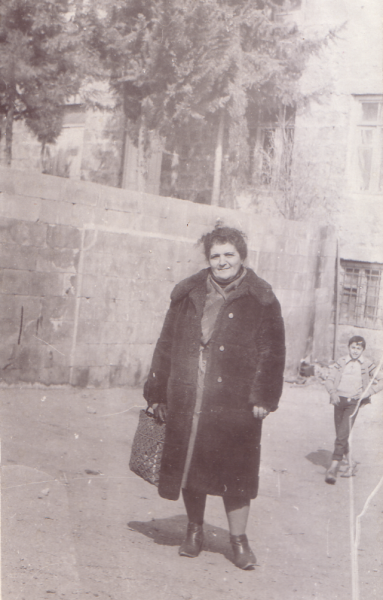

My grandmother, Arusyak Balasanyan, in 1940 in Tbilisi

My grandmother, Arus, was born in 1930 in a poor village in Meghri, Armenia. She was only four years old when her wealthy uncle from Tbilisi came to visit. The uncle, Grikor, saw that his brother was struggling to support his wife and four young children. Grikor and his wife had three sons but wanted a daughter. Grikor asked his brother whether he could take one of his daughters and raise her as his ward. They decided he would take Emma, who was three years older than my grandmother and the oldest daughter, and announced it to the family.

Don’t take Emma! She’s a dummy! Take me instead!

So my grandma moved from the squalor of her hometown to the home of her uncle, a jeweler. I remember her telling me how much she loved her uncle and his wife and their three sons, whom she loved like brothers. The oldest son was the only one who followed the rules, becoming a colonel during World War II. The middle son speculated on the black market, and gave my grandmother her first pair of tights, a luxury item worn only by the well-connected Russian women in Moscow. The youngest brother ran an underground bookshop, buying and selling forbidden books. It’s not surprising, then, that my uncle did not tell his sons where he had hidden his stash of precious jewels. He did not even tell his wife. He only revealed the hiding spot to my grandmother when she was 11 or 12 years old. After his death, his wife and sons upturned every tile searching for the jewels. Arus, think hard now—did Uncle ever tell you where he hid his jewels? My grandma finally remembered that, yes, her uncle had said something about hidden jewels. But she did not remember what exactly he had said. Quick-witted she may have been, but she was too innocent to think it would do her any good to remember where “x” marked the spot.

Meghri, 1985

***

The weak-willed and the lazy did not do well in the Soviet Union. The best things went to the richest people by default, and the leftovers were few and far between, so you had to hustle. My grandma never did an illegal thing in her life but she was a hustler nonetheless.

It was 1978, and my uncle was a young man just starting to serve his mandatory two years in the military. He was in Irkutsk, and his novice training there was about to end. He called my grandmother.

If you don’t come here and take care of these officers, they’re going to send me to Chita, or some other godforsaken city where soldiers go and don’t come back.

He was her first-born; she would do all she could. She would “take care” of these officers with bottles of expensive Armenian cognac, and basturma, soujoukh, sweet walnut soujoukh, dried figs, dried persimmons, dried apricots, and jars of fig murabba. All this she made with her own hands, somehow finding time between raising her children and working full-time. She packed these in a luggage or two, and left Meghri for Irkutsk.

What she brought to Irkutsk worked: my uncle was sent to Novosibirsk, the “Moscow” of Siberia, for the remainder of his training. But what my grandmother bought back from Irkutsk ended up being more special. One of her suitcases carried five huge pineapples – a fruit most Soviet Caucasians had never seen. The day after she got back to Meghri, my grandma peeled and chopped all five pineapples. One by one, all of the neighbors came to examine the prickly skin and enjoy the tart, yellow flesh of the exotic fruit.

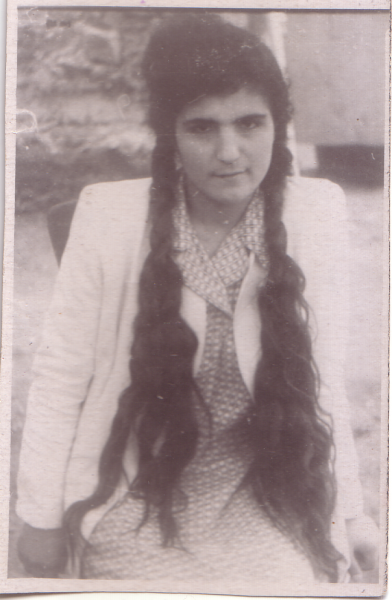

Yerevan, 1951. Long braids are a symbol of feminine beauty in Armenia and the Caucasus. Folk songs, old and new, reference a woman’s “մետաքս հյուս” (silken braid) to tell of her beauty. The braids here are merely attached for the sake of the photograph

***

I was too busy soaking in the faces of my aunt and cousin that first night to think about any practical matters. We had reunited in my grandmother’s apartment in Meghri, though it was no true reunion because I had never met my aunt and cousin before that day. My brother and I were in Meghri for the second time, and they had come from Moscow, where they had moved after the Soviet Union collapsed and life in Meghri had become unbearable for a young family.

But evening did fall, and the summer cool set in, and my mother called from New York. I told her the trip had been fine and we were at home.

Did you figure out the sleeping arrangements?

I hadn’t even thought about where we would sleep in my grandma’s small one-bedroom apartment. The bedroom had separate single beds, in the old tradition, where my grandma and grandpa normally slept. My grandpa was already asleep in his bed. There was a futon in the living room that could fit two, and my grandma had opened a lezhanka (Russian for “cot”) in the living room that would fit one. I turned to see that my grandma had laid out a thin little mattress on the bare floor in the bedroom.

Don’t you let Grandma sleep on the floor! I know her – she is going to want to be the one who has to sleep on the floor, but don’t you let her.

My grandma would have me sleep in her bed, and my brother, who was the youngest and lightest, would sleep on the lezhanka. And she would, as my mom predicted, sleep on the floor. I hesitated to argue with my grandmother – I was so inclined to obey her. But it would be “amot” or shameful to let her sleep on the floor, especially after my mother had directed me not to let it happen. So I refused.

Grandma, you should sleep in your own bed, and I’ll sleep on the floor.

No, no, that won’t work. You’re almost a woman grown – you’re not sleeping on the floor.

Alright, I’ll sleep on the lezhanka. I love lezhankas. Remember when you came to New York and I slept on the lezhanka for an entire month and loved it? And my brother will sleep on the floor – he’s young, it won’t make a difference to him.

I said no! No grandchild of mine is going to sleep on the floor in my home.

I grabbed her shoulders gently – even as a petite 16 year old, I was several inches taller than she was. Grandma, please, it will be better this way. You need your rest in your own bed. My aunt came in to see what the fuss was all about and lent me some support. My grandma finally agreed, and I fell asleep feeling proud that I had managed to convince her.

I woke in the morning to smells of breakfast. My grandmother was already up and working in the kitchen. I went into the bedroom to find my brother sleeping comfortably in my grandma’s bed. What’s this! I marched into the kitchen and confronted my grandmother.

Did you sleep on the floor?

Yes. I asked him if he wouldn’t rather sleep on the bed and of course he preferred it, so we switched.

I almost had a mind to shout at my brother, but decided he was too young to understand anything about amot, or respect, or sacrifice. And I dreaded the next time my mother would call because I would have to tell her that my grandma had gotten her way.

***

From this time of year and on until the end of summer I think about my grandma a lot. I remember her often, but the memories and longing rise from a simmer to a boil in the warm months, probably because it was always in the summer that I saw her. Did I tell you she taught me to read and write in Russian? It was a funny thing learning to read and write in a language I hardly knew. She was a Russian Language and Literature teacher in Meghri for many years, and had private students even after she retired. I remember when we would go walking outside and she was like the mayor—former students of hers, already grown adults, would greet her respectfully by addressing her with a teacher’s title.

From this time of year and on until the end of summer I think about my grandma a lot. I remember her often, but the memories and longing rise from a simmer to a boil in the warm months, probably because it was always in the summer that I saw her. Did I tell you she taught me to read and write in Russian? It was a funny thing learning to read and write in a language I hardly knew. She was a Russian Language and Literature teacher in Meghri for many years, and had private students even after she retired. I remember when we would go walking outside and she was like the mayor—former students of hers, already grown adults, would greet her respectfully by addressing her with a teacher’s title.

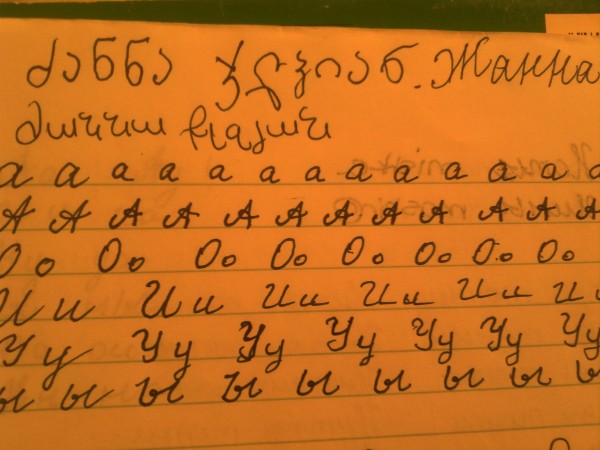

She came to New York the summer of my fourteenth birthday and she wanted to teach me Russian (she had taught me to read and write in Armenian the last time she had come to New York, when I was five or six years old). I’ll never say no to learning a language. So we would sit at the kitchen table everyday, weekends too, with a букварь (Russian children’s alphabet book) she had brought with her and a green spiral տետր (Armenian for “notebook/pad”). The above photograph is the first page of the տետր. The words on the top line are written in her own hand – they are my name in Georgian (which my grandma was also fluent in) and Russian. The Armenian I wrote myself to show her I still remembered.

***

In memory of my grandmother. Thank you to my mother, who has never refused to re-tell a story about her.

This essay is part of a series written in honor of International Women’s Day and Month.

Janet was born of the mountains, and was raised on the island of Queens, New York, where she now studies and lives. She loves folk songs, fantasy fiction, and the law. Also television.