Work, Happiness and Women in the Caucasus

While there are numerous gender inequalities to discuss in the Caucasus, this year, let’s focus on women and work. Certainly for biological and cultural reasons, less women work than men do, but for the women who do work, are they happy there?

(All differences noted are statistically significant. Data is Caucasus Barometer 2012.)

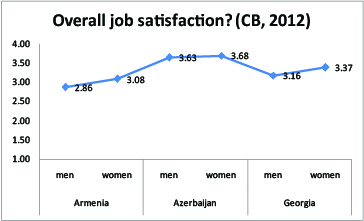

When asked about their satisfaction with their work (on a scale of 1-4, 1 being completely dissatisfied and 4 being completely satisfied), working women in the Caucasus were always more satisfied than working men. (And notably, Azerbaijanis are the most satisfied overall, followed by Georgians, and then Armenians.)

So why are Caucasian women more satisfied with their jobs than men?

Perhaps it is because men HAVE to work, whereas women that work likely come in one of two types: those that HAVE to work to financially contribute to the household and those that WANT to work.

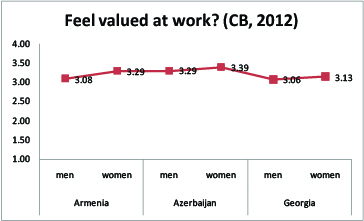

But what about feeling valued at work? Caucasian women do feel more valued at their workplaces than men do. And again, Azerbaijanis are higher than everyone else.

Are women carrying heavier loads at work and getting kudos for it? Globally women do tend to take on all sorts of burdens in the work place, but based on my limited experience in Caucasian workplaces, I don’t see women being “valued” in the workplace in terms of praise and rewards. However, compared to the high expectations placed on women in the home environment, the amount of praise and compensation Caucasian women receive in the workplace must feel good!

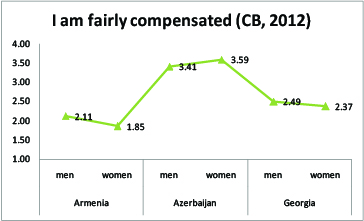

Speaking of compensation, this is a mixed story. Perhaps unsurprising, Azerbaijanis feel that they are better compensated than either Georgians or Armenians are. But while Armenian and Georgian women feel significantly less like they are fairly compensated than Armenian and Georgian men are, Azerbaijani women come out on top for compensation.

A smaller percentage of Azerbaijani women work than in Armenia or Georgia, so perhaps those women are more in the “want to work” than the “have to work” category? Also, based on what I’ve read about Azerbaijani gender relations within the household, there are greater expectations on Azerbaijani women for household duties, so it is possible that the working women feel the value of their compensation more.

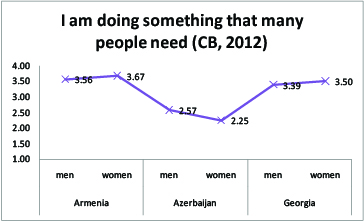

But how do women feel about the work that they are doing and the value to society? Again, there is a mix. Armenians and Georgians tend to feel that their work is contributing to something people need, while in Azerbaijan this is not the case. I attribute this to the lower unemployment in Azerbaijan – jobs are not as scarce as in Armenia or Georgia. But for the gender dimension – Armenian and Georgian women are more likely to feel that they are doing something that people need, while Azerbaijani women are less likely than men to feel that they are doing something that people need.

—

A quantitative analysis of the working world for Caucasian women is insufficient to completely understand the dynamics. Nonetheless, based on these analyses, it seems that in general, Caucasian working women are pretty satisfied with their work but do not feel that they are being compensated fairly.

Do Caucasian women have all the employment opportunities that Caucasian men do? Highly unlikely. Regardless, the satisfaction with work amongst women in the Caucasus is something to be optimistic about and to celebrate this 8 March.

Katy E. Pearce is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Washington and holds an affiliation with the Ellison Center for Russian East European, and Central Asian Studies. She specializes in technology and media use in the Former Soviet Union. Her research focuses on social and political uses of technologies and digital content in the transitioning democracies and semi-authoritarian states of the South Caucasus and Central Asia, but primarily Armenia and Azerbaijan. She has a BA (2001) in Armenian, Arabic, Persian, Turkish & Islamic Studies as well as American Culture from the University of Michigan, an MA (2006) in International Studies from the University of London School for Oriental and African Studies, and a PhD (2011) in Communication from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and was a Fulbright scholar (Armenia 2007-2008).

This post is part of a special series in honor of International Women’s Day