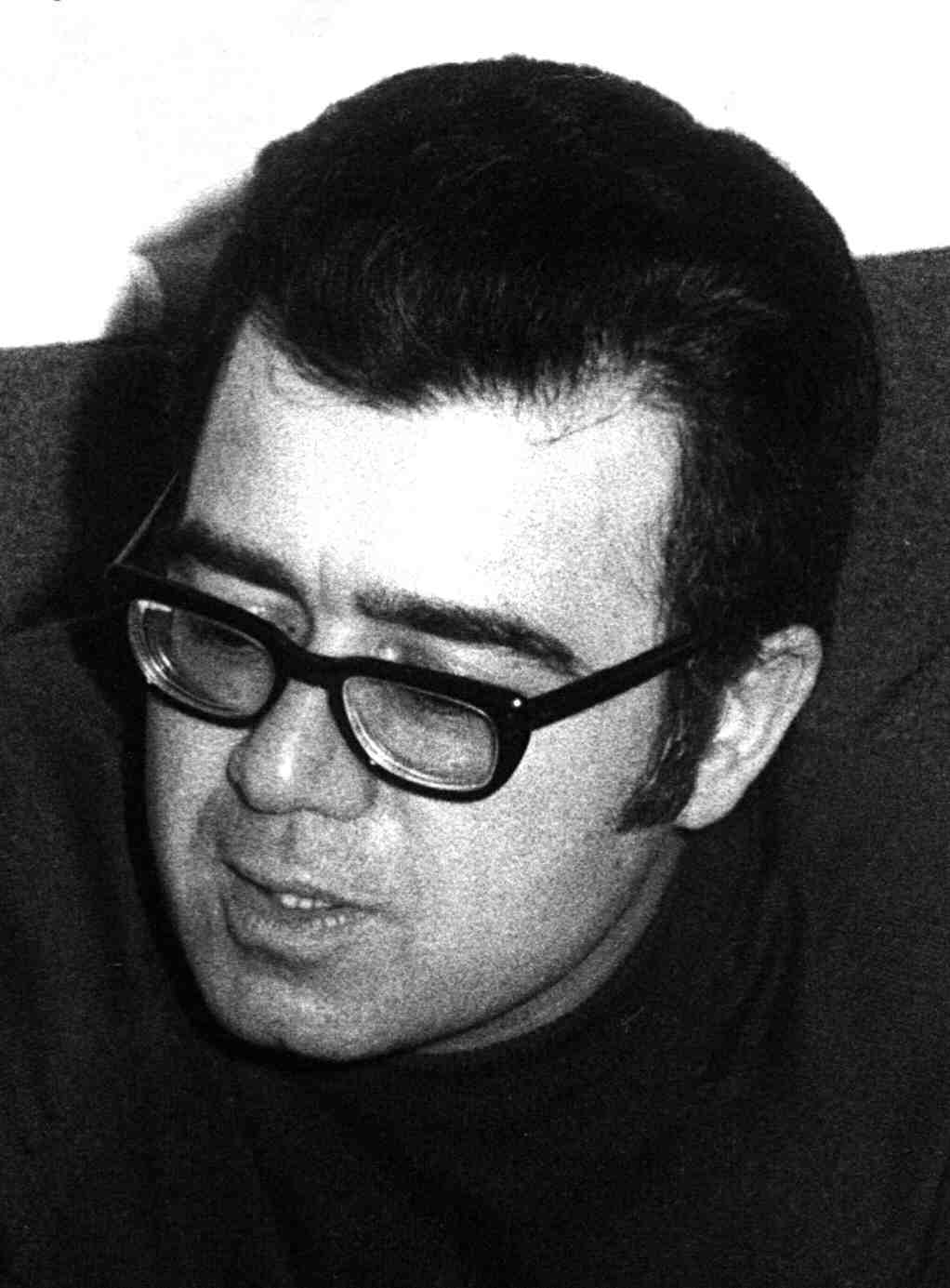

Interview: Writer Ara Baliozian

“A writer’s two best assets: the sensitivity of an open wound and the hide of a rhino,” writes Ara Baliozian on his blog, which houses his daily thoughts on topics ranging from religion, to money, politics, literature and of course Armenian matters. An author and translator, Baliozian’s writing has received a fare share of criticism from Armenian readers, but that doesn’t stop him from dishing out criticism and commentary.

Baliozian, born in Greece and educated in Venice, now lives in Kitchener, Canada and has published dozens of books, including “Armenians: Their History and Culture” and “In the New World” and translated many others. He now mostly posts his works on various Armenian internet discussion boards, but took the time out to answer some pertinent questions.

Q: My first question is simple, but perhaps it does not have a quite so simple answer: Why do you write?

A: I write because writing has become a habit and habits, as you know, are easier to keep than to give up.

Q: What is the best advice you can give to an Armenian writer like me?

A: Be honest with yourself and your readers. Do not accept anything on anyone’s authority. In our environment, the higher they rise, the bigger the lies.

Q: Many writers of your generation, whether they’re Armenian or not haven’t adapted to the web as easily as you have. How and when did you start using the Internet to share your writings? What made you do it?

A: I owe my use of the Internet to my good friend Noubar Poladian, who would visit me from Toronto (a distance of 60 miles) regularly in order to teach me how to use the computer even when I said I had no interest in abandoning my old typewriter.

Q: What sort of writing rituals do you have, if any? Is there a specific time of day you write or a place?

A: I write very early in the morning when everyone is asleep and it’s dark outside. I write no more than a single page. I may make notes during the day, most of which I reject in the morning.

Q: What are your thoughts on the protocols between Armenia and Turkey and how do you feel about those in the diaspora who are campaigning against the protocols? If you don’t agree with the protocols, what is the alternative? And what do you feel is the best way for the diaspora to express their concerns?

A: I am all for friendship with our enemies on the grounds that we may get more concessions from them as friends rather than enemies. May I say that I do not take the protocols seriously. But they are a beginning,which is better than no beginning at all. The Homeland and the Diaspora have different priorities. it would be selfish of us to assert our priorities are superior or more urgent than the Homeland’s. Live and let live. Let the Homeland take care of its own. The Turks already know that Armenia does not represent the Diaspora. As for our own concerns: I think the Turks know about them too. If it’s their intention to divide us, let us not fall in their trap.

Q: What kinds of concessions?

A: We could begin by asking the Turks to allow us to take care of our antiquities in Ani, Van, and elsewhere. About territorial concessions: it seems to me if we move in the direction of some kind of Union or freedom of movement within a United States of the Middle East or the Caucasus, the borders of historic Armenia and Azerbaijan may become an irrelevance.

Q: You’ve had your fair share of criticism from many Armenians who disagree with your writings and opinions and have even gone so far as to insult you on many occasions. How do you deal with this and what is it about what you write that upsets Armenians?

A: As a rule, I am insulted by brainwashed readers who have been exposed to countless sermons and speeches but not a single writer. What upsets them is the fact that I refuse to recycle chauvinist propaganda. Things like the Battle of Avarair (which even some of our own historians say it never happened), first nation to convert to Christianity (the real question is: have we ever been good Christians?), first nation to be targeted for Genocide? (why brag about that?) We are smart? In politics we do not even qualify as retards.

Q: You recently wrote on your blog: “I believe the Genocide to be a result of two colossal blunders committed by nationalist fanatics and fools on both sides. It goes without saying that to massacre innocent civilians is a far more serious crime than stupidity or ignorance.Ignorance may be the most innocent of all transgressions but in life it is the most severely punished. If there are inflexible laws in life, this surely must be one of them. And speaking of inflexible laws, here is another: If you refuse to learn from your blunders, you condemn yourself to repeat them. What have we learned from our genocide? What else but to say we are at the mercy of inevitable historic conditions or forces beyond our control? Same mistake, same propaganda, same Big Lie fabricated and recycled by men who are too lazy or stupid to think for themselves.”

Can you explain this a little further – what have been the biggest blunders of the Armenian culture as a whole? How do you feel we can make progress?

A: Our big mistake — or rather the mistake of our revolutionaries — was trusting the verbal commitments of the Great Powers. The idea that their support made us invulnerable. In international diplomacy verbal commitments, even treaties, are worthless if you don’t have the power to implement them.

Our second big mistake is to ascribe our present misfortunes (exodus from the Homeland, and assimilation in the Diaspora — also known as White Genocide — to social, political, and cultural conditions beyond our control…that is to say to assume a passive stance, instead of assuming an active role by getting organized, enhancing our solidarity, ending internecine conflicts and divisions.

Q: Do you have any regrets, either professionally or personally?

A: One of my greatest regrets is that I waited until I was 30 before dedicating my full time to writing.

I should have done it sooner.

Q: Who are your heroes in life?

Q: Who are your heroes in life?

A: Plato, Gandhi, Thoreau…to mention only three among many others.

Q: If you can pinpoint anyone, who would you say are the best role models/leaders within the Armenian community that Armenians can learn a lot from? Or if you think none exist, can you explain why?

A: We can learn a great deal from our writers — Naregatsi, Raffi, Baronian, Odian, Zohrab, Zarian, Massikian… I don’t know anyone alive today who can come close to them, alas!

Q: Why do you think it is so difficult for Armenians to have a fair and reasoned civil conversation without confrontation, bias or judgment?

A: The brainwashed tend to be dogmatic, that is to say, intolerant, and the intolerant cannot engage in dialogue; they prefer to sermonize and speechify.

Q: When you’re not writing, what do you do in your spare time?

Nothing gives me more pleasure than playing Bach on a pipe organ.

Q: As someone who decided he wanted to be a writer, you could have easily not

written about issues concerning Armenians. Why did you decide to?

A: I began by writing and publishing fiction, for which I was awarded several Canadian literary prizes and government grants — until I realized that the aim of fiction is entertaining the bourgeoisie. To understand and explain reality: that is what I want to do now…and I enjoy it better than writing love stories or, in Sartre’s words, about “the mutual torments of love.”

Q: What are your favorite books?

A: In Armenian: Zarian’s TRAVELLER & HIS ROAD.

In Russian: Turgenev’s FATHERS AND SONS.

In English: Toynbee’s RECONSIDERATIONS.

In French: Sartre’s LES MOTS.

In Greek: ZORBA THE GREEK by Kazantsakis.

Q: What are your favorite Armenian foods?

A: I am a vegetarian.