Sucheng Chan: A Great Woman, a Great Pillar

“I realized that the way I think about myself may differ considerably from the way others perceive me.” Sucheng Chan, 1989

For much of history, the popular imagination identified “greatness” with the exploits of powerful Anglo men. This greatness, however, was predicated on the marginality of women, underrepresented minorities while also obscuring the unique contributions of these populations.

For much of history, the popular imagination identified “greatness” with the exploits of powerful Anglo men. This greatness, however, was predicated on the marginality of women, underrepresented minorities while also obscuring the unique contributions of these populations.

Over the last century women have helped knock down the gender barriers to greatness, yet even as they did so, they often left racial and class barriers to greatness intact. Enter Sucheng Chan, a woman who achieved greatness by embracing her unique qualities including her status as an immigrant, her physical disability and her work as an intellectual. In the process, Sucheng Chan has helped knock down obstacles to the recognition of greatness in other marginalized peoples.

Sucheng Chan, was born in Shanghai in 1941 and was schooled in China, Hong Kong and Malaysia. As an adult she headed to the United States to earn a B.S. in Economics from Swarthmore in 1963, an MA in Asian Studies from University of Hawaii in 1963, and eventually a PhD in Political Science from University of Calif., Berkeley in 1973. This was unheard of for her era for a women let alone someone who had so many marginalities such as race, gender and foreign status. Chan parlayed this education into an academic career, eventually obtaining tenure at University of California Berkeley. She later moved to the University of Calif., Santa Cruz where she was a professor of history and where she also served as provost, becoming the first Asian American to hold this position in University of California history.

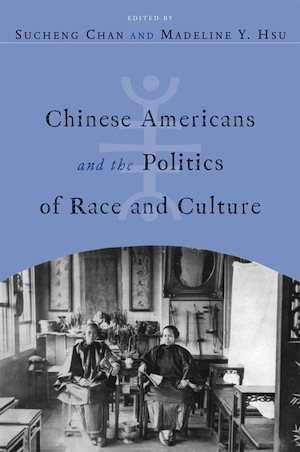

Chan was also a productive academic. A self-taught historian, she wrote and co-edited 17 books. Her success in the academy as a writer, professor and administrator have led many to see her as one of the “founding mothers” of Asian American studies. One of the strengths of Chan’s scholarship is her discussion of identity among people who must negotiate multiple marginalities. Chan contracted polio at age four which has led to a lifetime struggle with mobility and pain. In her 1989 seminal article, “And Your Short, Besides” Chan discusses her bicultural struggles with being differently-abled. For example, she recounts how her Chinese father always blamed himself for her physical ailments. He thought it was karmic retribution on his daughter for his wayward youth. For her part Chan met her disability head on including teaching herself to walk with crutches and excelling academically. As a youth during a piano recital in Malaysia an audience member screamed out that she was a cripple and should not be allowed to play. Despite the verbal assaults she finished her piano piece. In these trying moments she came to see how different cultures reacted to her disability. In Asia there were some people who tried to link her polio with being morally flawed and tried to convert her.

Americans, she says, sometimes ignore handicapped people to the point of not seeing them at all. In the United States she was beset with other forces. After wining yet another teaching award she bumped into a professor who had been her advocate for two decades. She reminded him that he told her to go into research instead of teaching. This kind-hearted professor, like other well meaning individuals can sometimes limit a differently- abled person’s potential. Chan goes on to say that Americans tell their children to look away when a handicapped person is in their midst. Asians, on the other hand may ask questions to learn more about your physical ailments. In her marriage, her future mother-in-law was worried that she would never be able to have any children. Her future father-in-law was concerned that his son did not marry a more physically attractive woman. The larger point here is that at every stage from academic to personal Sucheng has been met with significant barriers. Not concerned with any of this Sucheng wore a mini-skirt on the day of her wedding. Chan recommends that you ask questions to the disabled and accommodate to their wishes.

Americans, she says, sometimes ignore handicapped people to the point of not seeing them at all. In the United States she was beset with other forces. After wining yet another teaching award she bumped into a professor who had been her advocate for two decades. She reminded him that he told her to go into research instead of teaching. This kind-hearted professor, like other well meaning individuals can sometimes limit a differently- abled person’s potential. Chan goes on to say that Americans tell their children to look away when a handicapped person is in their midst. Asians, on the other hand may ask questions to learn more about your physical ailments. In her marriage, her future mother-in-law was worried that she would never be able to have any children. Her future father-in-law was concerned that his son did not marry a more physically attractive woman. The larger point here is that at every stage from academic to personal Sucheng has been met with significant barriers. Not concerned with any of this Sucheng wore a mini-skirt on the day of her wedding. Chan recommends that you ask questions to the disabled and accommodate to their wishes.

Today Sucheng Chan is an emeritus professor from the University of Calif., Santa Barbara where she was chair of the Asian American studies department. The consequences of polio continues to limit her mobility which has translated to accepting fewer speaking engagements. However, she continues to publish profusely. Sucheng Chan’s marginalities have not stopped her from making her life a metaphoric pillar for the Asian, Asian American, and American community. She cannot be defined in simplistic terms. As a pioneer in Asian American studies as a scholar, teacher and administrator she has not only laid claim to her own greatness but has also inspired new generations of marginalized people, be they Asian Americans, women, immigrants or physically disabled to chart their own paths to greatness.

Jenny Banh is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at University of Calif., Riverside. Her previous research at UCLA and CGU were on Asian American female gang members and Thai sweatshop workers. Her most recent publication was a book chapter titled, “Barack Obama or B Hussein: A post racial debate on Boston Legal” in Iconic Obama.

This post is part of a special series in honor of International Women’s Day