The Incense and Me: An Armenian (Grand)father’s Day Tribute

Holidays, except for the trifecta of Halloween, Thanksgiving and Christmas, aren’t major occasions in my family. There are no 4th of July bbq-drenched celebrations, no Valentine’s Day exchanging of gifts and no Memorial Day outings to monuments or events to honor the war dead, even Mother’s Day and Father’s Day are low key get-togethers, if anything at all.

And while I yelled “Happy Father’s Day!” to my dad yesterday, we didn’t do anything particularly special.

But there was someone I felt a pull to pay a special visit to, buried many feet beneath the ground, on the luscious green grounds of Forest Lawn somewhere between Bette Davis and Liberace: my grandfather.

I’ve written about him before, and while it’s been more than a decade since he left to go live among the spirits on Ararat, the memories he left with me during my childhood have not yet faded away.

There was the hand knitted hat he used to wear to go to sleep, his almost hairless head grasping for warmth at night, the hammer he kept out in the backyard from his shoe making days in Tabriz and Tehran which might as well have been an artifact in a museum exhibit. His yellow prayer beads, swaying back and forth between his worn hands which carried evidence of long afternoons in the garden tending to my grandmother’s treasured rose bushes, lemon trees and grape vines.

On summer mornings, with school out of mind and out of sight, I would accompany him to the local Middle Eastern grocery store, armed with list of supplies only to be found within the isles of stores owned by the descendants of the Cradle of Civilization.

He would tell me stories about life in Iran, his longing for Armenia and I would glide my hand across the pink and white railings while we walked back home.

My grandfather had emerged to Los Angeles with his wife and children, traveling thousands of miles, leaving everything he knew behind to come to America, and now he’s here in the Earth forever.

So on a refreshingly beautiful Sunday afternoon, I trekked down to simply say “hi.”

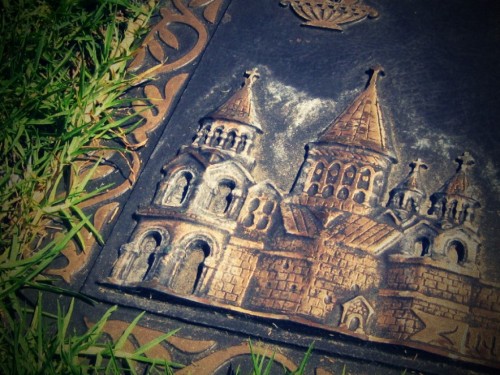

But an Armenian “hi” is anything but just, well, “hi.” Armenians are lovers of culture and tradition, and while I’m not particularly fond of American holidays for every single moment in history, the Armenian ones (at least a few of them anyway) seem genuine, a little less manufactured, dare I say, sacred.

A cemetery visit without khoong – that pungent incense used during church services doesn’t seem right.

When burned, the khoong’s rising smoke is said to represent “prayers going up to God.” The censer (poorvar/khoonganotz) is symbolic as well. It is the container that holds the incense, suspended by three chains symbolizing the “Father, Son and Holy Spirit.”Its two basic parts have different meanings, according to Pastor Nerses Manoogian of St. Gregory the Illuminator Church in Philadelphia.

“It has two basic parts; the lower, where the incense is burned and the upper. The lower part symbolizes the world. The upper part, which is dome-shaped, symbolizes heaven…So, when incense is burned in the censer, it is we, the inhabitants of this lower world, who are praying and our prayers are ascending to heaven with the intercession of the disciples. Poorvahr thus is the unity of heaven and earth with the union made by earth’s prayers and heaven’s receiving them.”

I’m not a religious person, so for me, the burning of the incense has never been connected to prayer. But religion and spirituality are two separate things, and as such the smoke symbolizes in the most simplest terms, the only tangible remains of my grandfather, burning away into the air and leaving behind the most fragrant of scents in my hair.

For tight-knit Armenian families, the death of a loved one is devastating, so when one goes, trying to keep their memory alive by any means possible is almost internally programmed. Our funerals and after funeral processions, which include a ceremony on the 40th day, on the one year anniversary, the passing out of halvah during the luncheon after the funeral, and if you’re really hardcore – the adherence to dark and somber clothing for weeks (or months) to pay respects, are steeped in tradition.

I could do without all of it, all the fuss and frill, except for the khoong and its not-of-this-world scent.

And for the five minutes that it burned near his grave, he was alive, spinning around me in a cloud of white smoke. The memories, suppressed by the mundane activities of daily life, came flooding back as if they had never left. And when it rose and disappeared and melted in the air, I knew that my grandfather had landed safely back on Ararat, home sweet home.