The Legend of Ali Baba: The Incredible Story of Armenian Genocide Survivor & World Wrestling Champ Harry Ekizian

By Liana Aghajanian

Some months after the long, treacherous deportations began, Mary Ekizian lost her husband Krikor to the horrors of the Armenian Genocide.

Driven to madness, she would often attempt to flee the caves she and her children hid in to escape detection from Turkish guards.

Every night her son Harry would wrap her long, thick hair tightly around his wrists as they slept, in an attempt to keep his mother close by.

One night she managed to break free.

Harry woke up to find her hair severed from his wrists. After checking on his sister, whom he had hidden safely away, he went to look for her. But the search to find his mother ultimately proved futile. He never saw her, or his sister who disappeared in the chaos, ever again.

The burden of these traumatic experiences would have left anyone wrestling demons for the rest of their lives.

Harry Ekizian however, would go on to wrestle for the World Championship title.

The genocide survivor who, as an old man, recalled witnessing Turkish soldiers beheading Armenians “like chickens,” serendipitously won the title on April 24th, 1936 – the annual commemorative date of the Armenian Genocide – and had one of the most successful wrestling careers in U.S. history, setting the precedent for the likes of Andre the Giant, Hulk Hogan and Ultimate Warrior as one of the first true gimmick wrestlers with his much-feared character, “Ali Baba.”

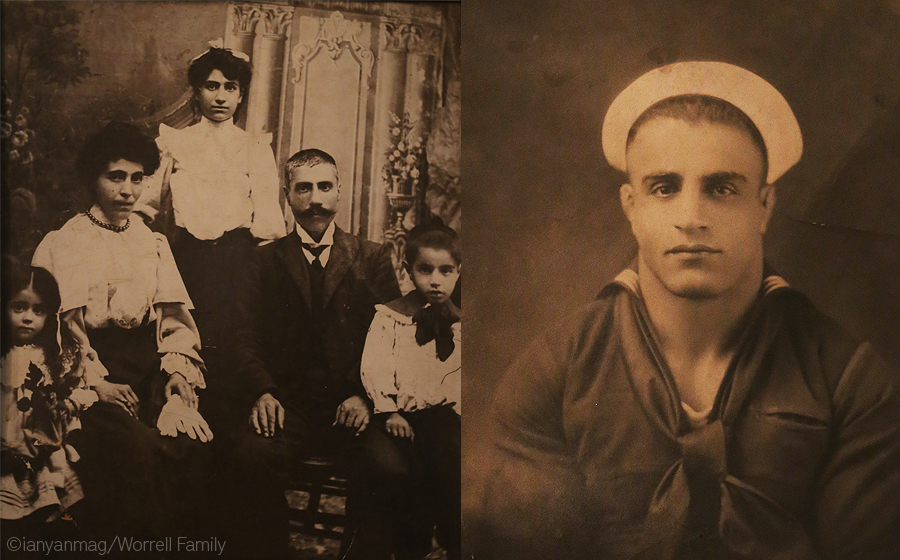

The Ekizian family in the 19th century, Ottoman Empire / Harry Ekizian during his deployment in the U.S. Navy (Photo: © Ianyanmag/Worrell Family)

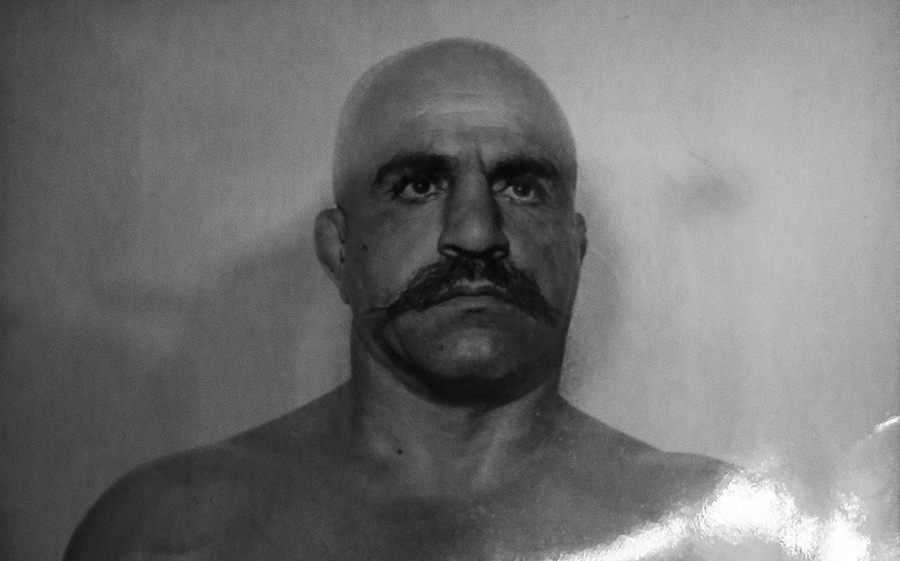

He was nicknamed the Terrible Turk, Break Em’ Neck Harry, the Krushing Kurd and Ali Yumed, but ultimately chose “Ali Baba” as his moniker. With a fez on his bullet-shaved ‘bald dome,’ the walrus-mustachioed former Navy man referred to as the “homeliest and fiercest looking individual in sports” was a success story both on and off the mat, headlining wrestling exhibitions across the country to large crowds and making cameos in several well known Hollywood films.

But while his persona helped define an era of professional character wrestling that eventually permeated pop culture, it was only part of who Ekizian was. A seasoned rancher, doting family man and steadfast Christian who always credited God with his survival from slave to ‘strong man,’ Ekizian’s agile hands once used to ‘crush’ his opponents became legendary in California’s Central Valley as he reinvented himself into a masseur, healing the aches and pains of migrant workers and business men alike.

“He looks ferocious in all these characters, but once you knew Ali Baba he was such a kind, gentle man, that’s what I remember about him,” says Beverly Keel Worrell, Ekizian’s daughter-in-law. Her late husband Gary who passed away in 2009, was Ekizian’s adopted son and grew up with the wrestler after he had retired from his career.

From Worrell’s home in Dinuba, Calif., just a few miles away from the citrus ranch where Ekizian spent the second half of his fruitful life, we talk about the wrestler’s tragic past to his inspiring resilience amid family photos and old newspaper clippings.

One in particular catches everyone’s eye.

“I was very powerful, nobody could believe it,” Ekizian is quoted saying in one yellowed, old clip on the table. “But God gave everyone something.”

It wasn’t just Ekizian’s strength, but an unflinching tenacity for life through both tragedy and triumph that truly made him a survivor.

***

Harry was born Arteen Ekizian in the Black Sea port town of Samsun in 1901 to a wealthy Armenian tobacco merchant who worked for the American Tobacco Company. His father Krikor traveled back and forth to America from Turkey, eventually earning American citizenship – a crucial precedent which later contributed to Ekizian’s safe passage to the U.S.

When the systematic attempt orchestrated by the Ottoman government to wipe out its Armenian, Assyrian and Greek populations began, Ekizian was only 14 years old.

Among the over one million deaths that have come to define the Armenian Genocide, he would later find out that his father had been hanged.

As his family began the long march to death without their patriarch, the trauma had only begun. Ekizian’s younger brother died of starvation along the way before he hid, with his sister and mother in nearby caves. After their disappearance, Ekizian was sold into slavery and forced into hard labor by his Arab captors. He survived by eating scraps and sleeping rough in the barns where they kept him without a bed or change of clothes.

Four years later, he eventually escaped and reunited with an older sister who was living in Constantinople.

With the help of his uncle Garabed, who lived in Dorchester, Mass. and was often essential in providing support to many Armenian survivors escaping the Genocide, Ekizian came to the U.S. in 1920 and soon started work in Garabed’s fish market.

Ekizian, though small in stature (various reports have him at no more than five feet six inches tall) had an unmatchable strength even from an early age.

“He worked in the fish market and my father said he could take a 600 pound barrel of fish and put it on the truck by himself,” says Charlie Ekizian, Garabed’s grandson who now lives in Florida.

If anyone was going to be a wrestler, it should have been Charlie’s father, who was also named Harry. Though he was at least 10 years younger than his cousin, he was built like a bear, Charlie recalls.

“He was a 280 pound mechanic who could pick up a car like a toy, whereas Ali Baba, he didn’t even look like [a wrestler],” says Charlie.

But while Charlie’s father showed no interest in the sport, Ekizian grew eager to get in to the ring.

After a few years of hauling seafood, Ekizian joined the U.S. Navy and saw active duty for two terms. It was here which he passionately took up the sport that forever changed the course of his life.

Harry Ekizan showing his astonishing physical abilities in a game of Tug of War with fellow servicemen. Needless to say, he won. (Photo: © Ianyanmag/Worrell Family)

In addition to winning the titles of Fleet Champion in middle weight, light heavy weight and heavy weight champions he was also named World Champion Navy Wrestler title at a match in Copenhagen, and honored at a White House Reception in 1927 by President Calvin Coolidge.

He would later be called the “Navy’s Strongest Man” in an old American pictorial magazine.

In 1932, after leaving the Navy and attempting to start his professional wrestling career, Ekizian came to Los Angeles where he found both love and fame. He married Alice Elizabeth Bagdoian, a Californian of Armenian descent with whom he had three children. The couple lived in Pasadena while Ekizian worked at a secondhand auto parts shop and made appearances in such films as “Island of Lost Souls,” and W.C. Fields’ great 1935 movie, “The Man On The Flying Trapeze” in which he played “Hookalakah Meshobbab” and grappled with Swedish wrestler Tor Johnson.

Harry Ekizian (left) in 1932’s “Island of Lost Souls.”

It was during this time that Ekizian’s took his innate strength to the professional circuit.

An April 1932 issue of the Southeast Missourian describes his debut:

“Enter the United States Navy champion in the professional heavyweight wrestling racket. Harry K. Ekizian of Watertown, Mass. spent eight years in Uncle Sam’s Navy and during that time he flopped all the gob wrestling champions of the United States, Italian, French, English, Turkish and Japanese navies. He was mat king of the middle, light heavy and heavyweight divisions. A match with Jim Londos is his aim.”

By this point, the wrestling profession was undergoing an evolution that would eventually heavily influence the outrageous and bombastic styles of World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. or WWE in the ’80s and ’90s. It shifted from the legitimate “catch-as-catch-can-style” dominated by wrestlers like Frank Gotch, who became the first American to win the world heavyweight freestyle championship to one run by regional carnival promoters looking to make quick and hefty profits. These carnies would for the most part transform the sport into a highly entertaining, theatrical and lucrative operation.

Mike Chapman, an Iowa-based wrestling historian and former wrestler who has written 15 books on topic, says the drawn out matches of the early 20th century which took hours and put wrestlers out of work if they were seriously injured went under refinement. A wrestler’s success soon depended on how many seats he could fill and the number of matches he could consistently compete in.

Ekizian, with his menacing look and genuine strongman skills refined under an almost decade long Navy career, would have been a promoter’s dream.

“There’s no question he was a superb athlete and a very powerful man,” says Chapman. “That’s one of the things promoters would look for, somebody who looked the part and if they could actually fit the part it would be better. These fellows really put on a show, they could draw a crowd.”

It was at a much anticipated match in Detroit, Mich., on April 24th, 1936 in front of over 8,000 spectators which put Ali Baba, complete with fez, mustache and frighteningly ‘foreign’ appearance, on the wrestling map forever.

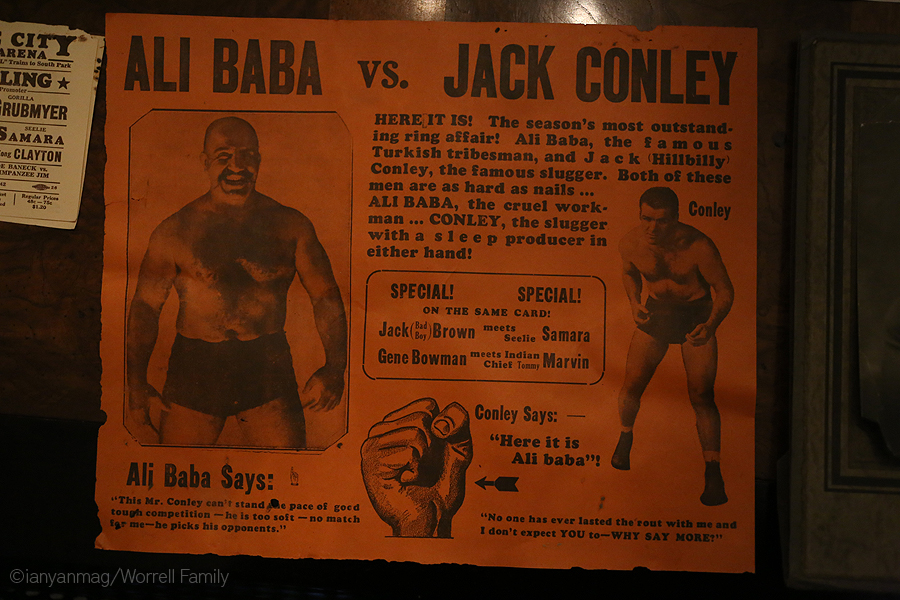

Ali Baba memorabilia from the Worrell family’s collection (Photo: @ Ianyanmag/Worrell Family)

Ekizian’s defeat of Prussian-born Dick Shikat for the title of Heavy Weight World Champion sent the press wild.

The New York State Athletic Commission, which controlled much of the wrestling profession did not recognize the winning and made Baba and Shikat duke it out on the mat again – this time in Madison Square Garden on May 5th.

Baba won and was formally declared World Champion.

“The Armenian Assassin makes Poor Shikat Bleed in Match,” wrote the Pittsburgh Press. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette summarized Baba as weighing some 212 pounds, “190 lbs of which is said to be stored in his angry mustache.”

In the May 6th, 1936 edition of the Lawrence Journal World Baba is described as a Terrible Teuton who flubbed Shikat “hither and thither with gusto and Babandon.”

“As Mr. Shikat lay there trying to remember if he had left the light on in the bathroom at home, Mr. Baba leaped upon him with a body press, and this week’s wrestling match of the century was over.”

As author Scott Beekman writes in his book, “Ringside, A History of Professional Wrestling in America,” Ali Baba’s claim to the title can be viewed as the beginning of the gimmick wrestling era.

In his colorful 32 year career, Baba managed to wrestle some 3,500 men, making up to $5,000 dollars a week during a time when the average person’s salary was less than $2,000 a year.

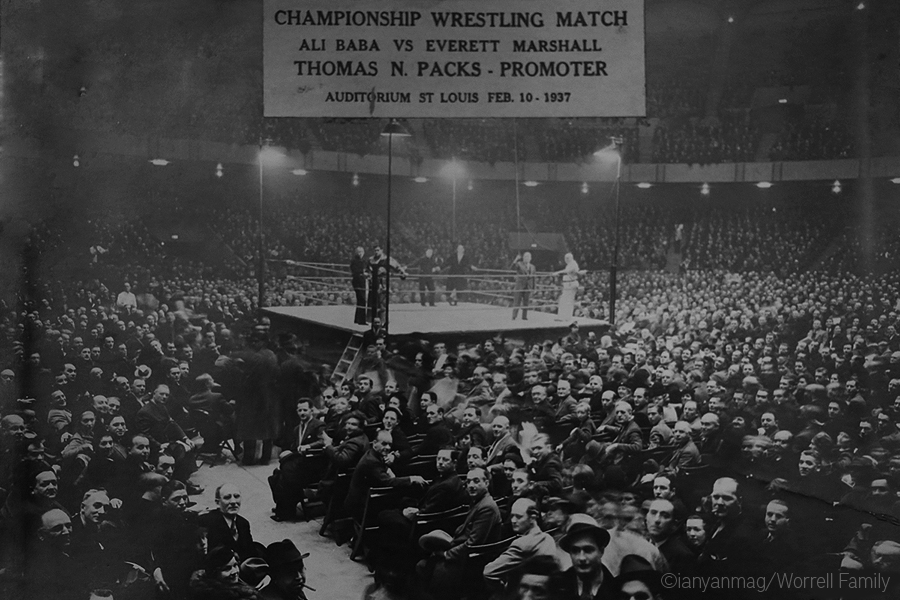

A packed crowd during a 1937 fight between Ali Baba and Everett Marshall, also known as “The Blonde Bear.” (Photo: © Ianyanmag/Worrell Family)

Sometime after the name Ali Baba had become well known around wrestling circuits, Ekizian and his first wife divorced. Financially strained, Ekizian took what money he had left and bought an old farm house in Sultana, Calif., where he began tending to his citrus groves.

He soon met and married Henrietta, a woman from Illinois whom he had first seen in a photo at her sister Helen’s house. Helen, along with her husband Sam were Ekizian’s neighbors and laughed at the prospect of their coupling.

But as the saying goes, opposites did indeed attract.

Henrietta was refined and educated, while Ekizian came across as a “rough and gruff type of guy,” Beverly Worrell says. “Henrietta was such a kind, gentle woman and she understood him completely. And he totally loved her, he would do anything for her. So they had such a wonderful marriage.”

Ekizian also took her adopted son Gary under his care. Though they had no blood relation, Gary went on to win numerous wrestling matches as a young man in high school and joined the Navy. It was clear that the only father he would ever know ultimately had a strong influence on his life.

Permanently planted in California’s Central Valley, Ekizian soon became a local, recognizable hero.

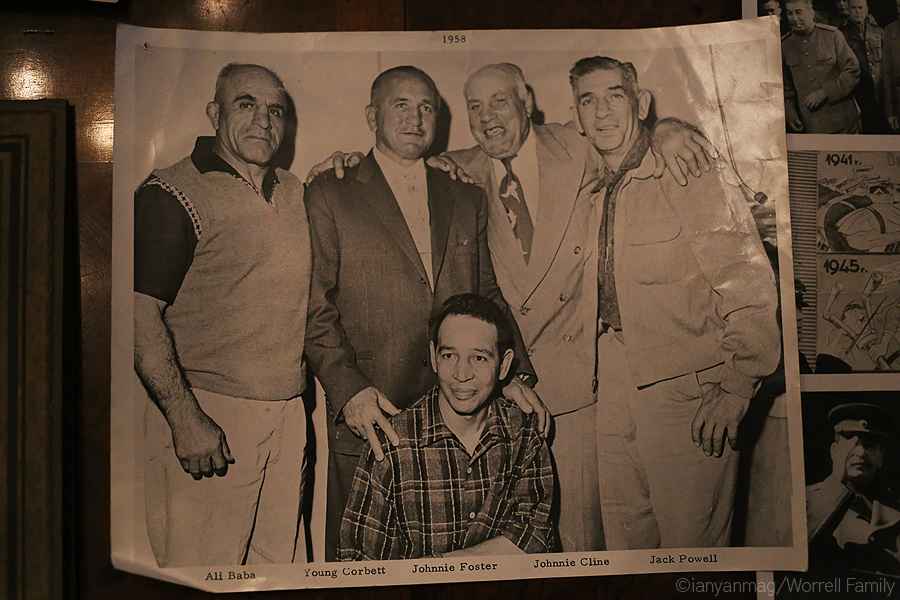

Ali Baba (left) with old sports colleagues in 1958 including famous boxer Young Corbett. (Photo: © Ianyanmag/Worrell Family)

Ekizian’s grandson Eric Ekizian, 47, who is Gregory’s son, one of this children from his first marriage remembers his strict regime.

“He would sunbathe after he’d ran 5 miles on the beach, done 1000 knee beds and 500 push ups every day until he was in his 70s,” Eric says.

His diet consisted of three cloves of garlic every day, parsley as well as hot lemon juice. He would also treat himself to an entire tub of ice cream, too.

He was also frugal and bartered constantly, traits ingrained in him since the hardships he endured as a slave.

“I’d heard from my dad that even when he was in his 70s, he would go to the dumpsters behind super markets and pull the fresh vegetables and take them home,” says Ekizian’s other grandson Garrett Worrell, 36.

And if he liked you, he’d call you a no good lousy punk – a title affectionately held by both his grandsons.

Without any formal training, Ekizian soon turned his wrestling talents into a new career as a masseur, taking the strength that could render his opponents helpless and channeling it through hands that healed.

First only taking donations and never charging more than $5 for a fix, he had customers coming all the way from Los Angeles to get their backs worked on in the massage parlor at his home.

“It wasn’t just the strength of a wrestler that he had, but it was a gift of the gentleness of those hands,” Worrell says.

Garrett remembers high school friends telling him how Ekizian would come to the aid of their migrant worker parents who spent all day toiling away in fruit fields.

“They remember Ali Baba coming out there daily and voluntarily adjusting all the field workers’ backs,” Garrett says.

Ekizian’s generosity and life has had a large impact on his fragmented family.

Grandson Eric, who was inspired by his grandfather’s masseur career, went on to become a chiropractor.

“When I would stay with my grandfather, I would go in and see people leaving with tears of gratitude,” he says of the clients Ekizian had. “That made an impression on me.”

Eric now has his own practice not too far away in Merced, Calif. “I had a heart for that because I saw my grandfather helping people,” he says.

Charlie Ekizian, who inherited Ali Baba’s strength and suffered from a spinal-cord injury from a diving accident when he was 21 has been a pioneer in the rehabilitation of people with spinal cord injuries through his organization, the Wheelchair Sports and Recreation Association. Ali Baba had always remained an inspiration for Ekizian, helping him move forward to help others despite his disability.

The Worrell family have established a wrestling scholarship in Ali Baba’s name at Dinuba High School in hopes of inspiring the next generation of wrestlers to carry the profession.

Before Ekizian died in 1981 from a massive stroke, he was also remembered for being a Genocide survivor who held no animosity towards Turks.

In an old local newspaper article from the 70s, Ekizian references the assassination of two Turkish diplomats by Gourgen Yanikian in Santa Barbara, Calif. Yanikian who lost over 20 extended family members in the Genocide, received life imprisonment for the killings.

“Ali Baba look what he’s done, he’s killed a Turk” he says he was told by fellow Armenians. “I say he was a coward, what he’s done was the worst thing.”

Beverly Worrell recalls speaking to him about the sensitive topic.

“He said it was a whole different generation, and that you can’t carry hatred towards a whole group of people.”

A devoted Christian, he spoke of his belief that any reprisals against perpetrators of the Genocide would be taken care of by the same higher power who was the source of his strength.

It was his faith which Baba believed gave him the ability to survive throughout bouts of despair, dexterity and endurance in the match that became his life.

“God always had angels behind me,” Baba said. “That’s what I believe.”

***

All photos and story © Ianyanmag.com/Worrell family. Please do not repost, republish or print or use without prior permission from Ianyanmag.com.

Liana Aghajanian is a journalist whose work has been published in the New York Times, Al Jazeera America and Foreign Policy among other publications. She is the editor of Ianyanmag. To see more of her work, visit her website.